Converging towards a Common Protocol of Organizing

Why the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Enabling Organization may be a breakthrough in organizational development. In this essay, we will go through the Micro-Enterprise, the Shared Services Platforms, and the Ecosystem Micro-Community Contract, among others.

Boundaryless Team

This essay is the first of a series that explores the potential to build a software ecosystem to support an emergent common model of organizing based on small units, shared services and dynamic contracting. This essay was written by Simone Cicero (Boundaryless) with contributions from Bryan Peters (Sobol.io), Rob Solomon (cone.network), Sascha Kellert (rekursive.org) and Emanuele Quintarelli (Boundaryless).

If you’re interested in contributing to this effort as an investor, you’ve developed a software solution in line with this model or you want to be informed about the next steps please check out the link at the end of the page.

The 3EO model can essentially be described as an organizational structure based on relatively small, unbundled, and self-directed units that cooperate dynamically through contracts and are supported by enabling constraints and shared services.

As we’ve had the chance to highlight already on this blog, we firmly believe that such an organizational model is ideal to – on one hand – confront the increasing complexity in markets and societies, and – on the other hand – take advantage of the plummeting transaction cost due to pervasivity of technology.

It’s intuitive how – In presence of a near-zero transaction cost – integrating vertically your organization into functional structures becomes less of a driver of competitive advantage: organizational capabilities such as a particular technology, a process, a certain set of skills can be reorganized quickly around customer-driven opportunities if the organization is “unbundled” enough to let its “building blocks” recombine fast.

While modularity and composability are recognized as enablers of fast recombination around new experiences (Joe Pine), industrial organizations have been optimized around production efficiencies and production supply chains as a consequence of high transaction cost: controlling suppliers (both external and internal) was a massive advantage facing predictable markets.

As we move forward, towards demand becoming more transient, more niche, the ability to serve the demand is becoming the “key control point” (Sangeet Choudary), and therefore embracing an organizational model that optimizes for low transaction costs becomes a natural organizational development direction.

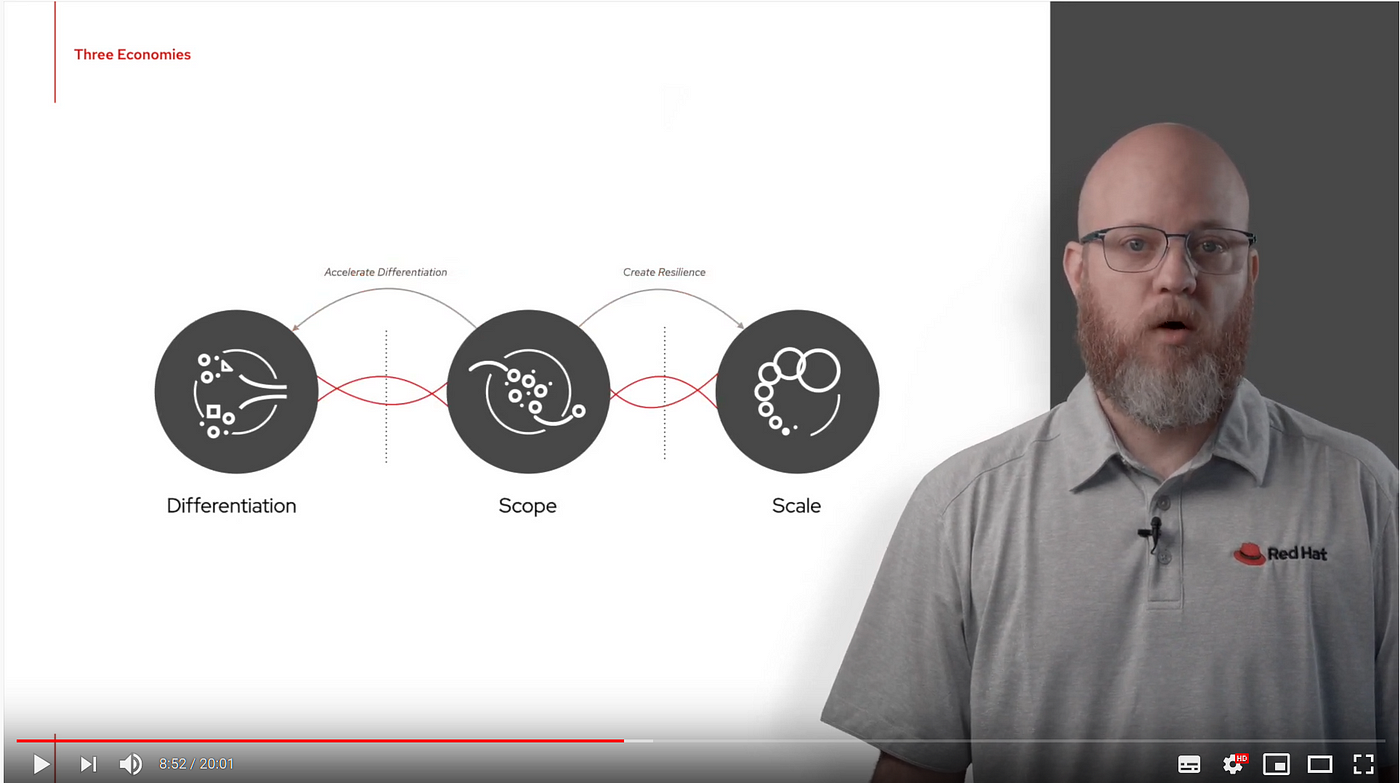

Adopting Red Hat’s Jabe Bloom’s view on this, we could say that by embracing such a model an organization is capable to deliver a synthesis between:

- economies of scale: that push for the need to consolidate functionally, integrate capabilities, regulate and control, consolidate, provide reliability in key essential elements of the business;

- economies of differentiation: that push to get fast in touch with customers, create novelty, let niche specialization of the solutions happen, and incubate the new;

through:

- economies of scope: that approach such friction optimizing the use of common resources, allow the negotiation of shared value (shared services), increase resilience through observability (thanks to the abundance of interfaces between the elements), variety and adaptability (dynamic contracting).

We believe that the market is now offering evidence comforting the hypothesis that this common model of organizing, through a set of common organizational artifacts can thus now be considered valid beyond one specific context, and need to be seen as dictated by the nature of markets and technological progress.

Check out this video and the recent podcast we had with Jabe.

By comparing a set of organizational models that leading progressive organizations have been adopting, embracing these principles, and positively impacting their development trajectories, it is now possible to isolate a number of basic artifacts that, to some extent, all organizations could draw on. This common grammar could possibly serve as a basis for the development of common software technologies that in turn could power the adoption of such organizational models, also facilitating cross-border interaction between organizations. This capability to drive more inter-organizational collaboration would allow organizations to more easily be able to thrive in changing environments, and could effectively lead to the transition from independent and competitive organizations towards a more general concept of co-operative organizing.

First of all, the basics

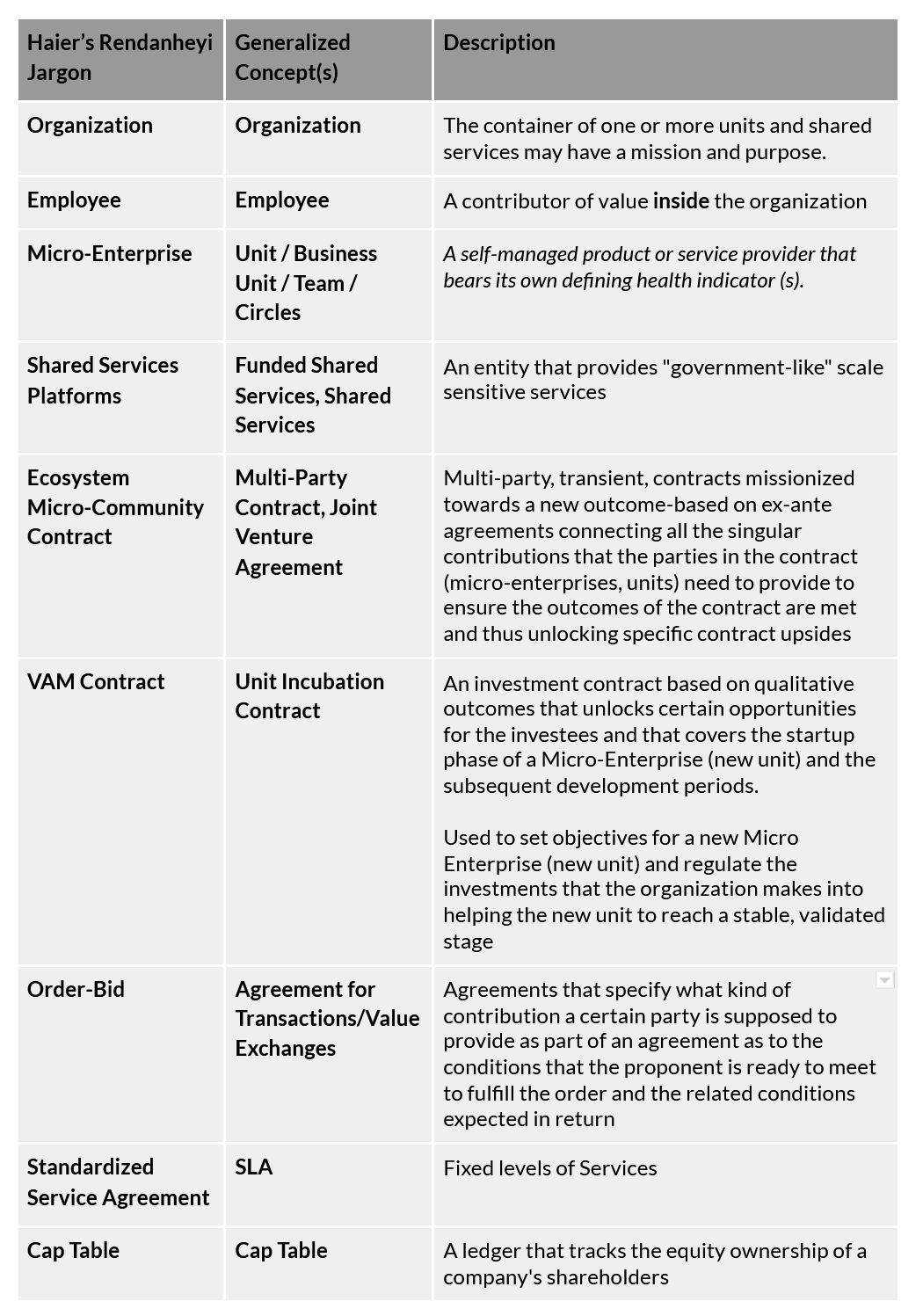

Here’s a list, and a description, of the basic artifacts that we believe constitute this sort of basic set of elements that make up the EEEO/3EO organizations. Most of them will be presented with the name they have in the context of Haier’s Rendanheyi — the most important inspiration so far for the EEEO/3EO framework and arguably the most advanced organizational model in the world when it comes to embracing the thesis presented at the opening of the post:

- the Micro-Enterprise;

- the Shared Services Platforms;

- the Ecosystem Micro-Community Contract.

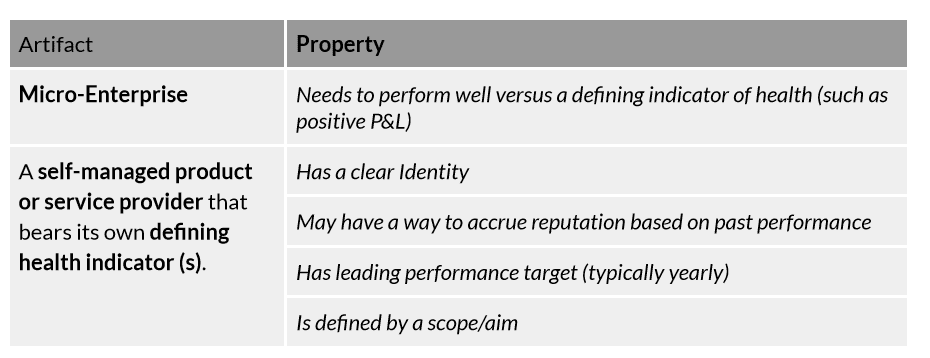

The Micro-Enterprise.

The Micro-Enterprise is a small unit (normally less than 20 employees) characterized by an identity (unique) and its reputation (based on the contributions it provided to partners) and it’s normally defined as a self-managed product or service provider that bears its own defining health indicator(s).

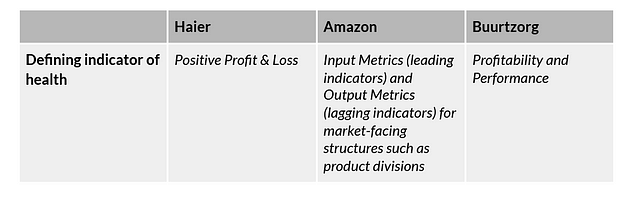

Normally having a positive P&L is the simplest health indicator that drives Micro-Enterprise development in the very same way it would if the Micro-Enterprise was not part of an existing organization but was alone in the market. Using the P&L as the defining indicator of health for a Micro-Enterprise – as in Haier’s Rendanheyi – is a powerful driver towards reducing technical and organizational debt that an otherwise bureaucratic structure would allow to accrue, as a consequence of optimizing for bureaucracy.

Other ways than forcing P&L have been used to develop “fit” Micro-Enterprises/Units/Teams. In the early 2000s Amazon embraced a structure based on the idea of having “2 Pizzas” teams, teams of a size that could be fed by just two pizzas, and asked those teams to provide a unique identifier of “fitness” (a fitness function): a simple equation (as simple as having positive P&L) that was to be optimized. The fitness function has been discontinued since then and now Amazon runs every department, operational team, and divisions on a fractal structure of so-called Input Metrics (controllable performance indicators that influence the business performance often called “leading indicators” in the industry) and Output metrics (directly related to business performance, as revenues, normally called “lagging indicators” in the industry), with performance reviews happening weekly and a yearly process called OP1-OP2 (more details here).

Buurtzorg instead — another famous organization that runs on small, independent but centrally coordinated units — provides yearly objectives to its units in the form of expected financial results and – more importantly – a target productivity.

The most recent expected productivity performance for Buurtzorg is 61% (read the transcript from the interview of Gertje Van Roessel here)

(A comparison of “forcing functions” as defining indicators of Micro-Enterprise/Unit/Team health)

Further elements that characterize a Micro-Enterprise are the leading targets and the aim. The aim is normally the definition of the scope, and overall raison d’etre of the micro-enterprise (for example the product it aims at delivering if customer-facing, the service that provides to other micro-enterprises, etc…) and the leading goal is somehow related to the yearly expectations, the performance targets. Not all these elements are always present in a micro-enterprise in all implementations.

As a recap:

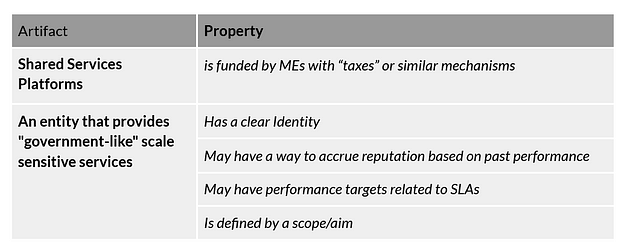

The Shared Service Platform

This artifact represents a sort of “government-like” service. SSPs normally cover centrally funded, basic functionally integrated services. The services most commonly served this way are the following: IT, HR, Legal and Finance, sometimes Marketing and other functions. Many times organizations chose to centralize some services for economies of scale reasons or for regulatory compliance. An SSP is still characterized by a defined identity and reputation. Services provided by an SSP may be protected from a certain level of monopoly (meaning that Micro-enterprises can only use SSP providers and can’t source such services on the market).

At Zappos — as described in the interview with John Bunch previously released at Boundaryless Conversations Podcast we ran in 2020 and on a more recent one with Rachel Murch — Bunch explained how it was possible for teams at Zappos to shortcut the waiting times for the consumption of SSP provided services, with the example of legal, but that the final approval was still given by the SSP (note that the interview was recorded in early 2020, things may have changed in the meanwhile).

In the case of internal monopoly, SSP are sometimes (and should overall be) subject to SLAs as they virtually represent a “single point of bureaucratization”: the level of SSP monopoly that is allowed inside an organization directly affects the risk of over bureaucratization and performance gap.

Another key example would be the use that Buurtzorg makes of a shared IT system that ensures overall alignment by aggregating all patients’ information and making it accessible from any device 24 hours a day. It connects teams to the back office streamlining reporting processes, invoicing, registrations.

Mechanisms to fund SSPs vary depending on how much the management of P&L is centralized or decentralized. As an example, Rendanheyi provides that SSPs receive partial centralized funding and partial additional funding is related tom additional services that the SSPs provide to Micro-Enterprises. Zappos, which also decentralizes P&L and enforces positive P&L, instead taxes all Micro-Entrepreneurial units based on the utilization of personnel (each “circle” using a person’s time will pay an amount that exceeds the organizational cost and pays for shared services). Buurtzorg instead manages P&L in a centralized way, imposes certain productivity to generate funding for the few centralized services it provides (mainly the centralized IT platform and the team coaching services).

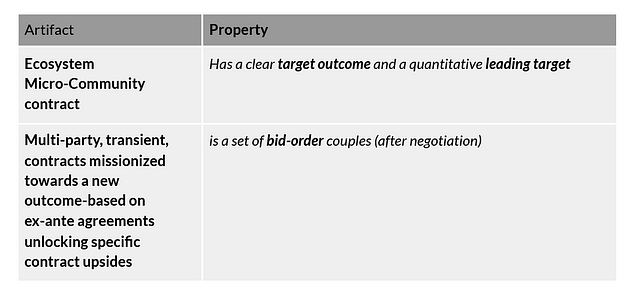

The Multi Micro-Enterprise Contract (the Ecosystem Micro-Community – EMC Contract)

The EMC contracts are rather specific artifacts rarely seen in organizations that are not part of Haier group. The EMC is indeed arguably the most innovative management and ODD (Organization Design and Development) contribution of Haier to management practices of the last decade.

The EMC is effectively a multi-party, transient, contract missionized towards a new outcome. The EMC is based on ex-ante agreements connecting all the singular contributions that the parties in the contract (micro-enterprises, SSPs and investors) need to provide to ensure the outcomes of the contract are met. The EMC also regulates the unlocking of specific “upsides” for example in terms of profits re-distribution.

The new outcome is a new “user scenario” in Haier’s jargon, essentially a new experience that can be provided to customers on the market and that will likely generate new profits. EMC contracts have the role to coordinate and ensure cooperation among otherwise very individualistic MEs, and to ensure the organization can bring to the market more complex value propositions that depend on the cooperation of many Micro-Enterprises.

This type of contract is needed to effectively re-bundle organizational capabilities into complex value chains: such objective would normally otherwise be attained by static, functionally and vertically integrated stable organizational structures in an industrial organization. By adopting these contracts an organization can successfully ensure that no sclerotization of organizational structures that are no more functional to produce market value are kept in place, thus keeping the organization lean and optimized.

At Haier, EMCs depends heavily on IT solutions that effectively reduce the transaction cost on contracting. A so-called “ EMC Workbench” (a software solution is provided to Micro-Enterprises in Haier) provides the possibility for EMC initiators to specify clearly: the EMC aim, a tangible leading EMC’s goal (in terms of measurable outcomes such as sales), and all the technical contribution needed by other MEs and SSPs inside the organization (in the form of “orders”, see below).

Following the specification of the needs, a negotiation can happen between the EMC coordinator (an ME) and the other MEs ensuring that all MEs agree on the expected conditions of returns in exchange for the provided service: as an example, an ME could commit certain production capabilities in exchange of a given percentage of profits.

To fully explain how EMCs work we need to introduce another couple of artifacts that are not specific to Haier but that are essential in the pruning of this basic model: the dual system of order and bids. An order and a bid can be seen as the two sides of a contract:

- the order specifies what kind of contribution a certain party is supposed to provide as part of an agreement;

- the bid specifies the conditions that the proponent is ready to meet to fulfill the order (for example the quality or quantity of the contribution – e.g.: producing 100k pieces in one month) and the related conditions expected in return (e.g.: a fixed lump sum, a % of profits generated by the outcome on the market).

Other key artifacts

The set of artifacts needed to complete the description of a 3EO, unbundled organization, including of course also:

- an Employee – normally identified by an Identity, a Reputation, and a graph of belonging to one or more Micro-Enterprises;

- an Organization – defined as the container of one or more MEs and SSPs and defined by its Identity, Reputation but also by its Vision and Purpose (in almost every case).

The Organization can be seen as a fractal, with one single organization defined as containing or being contained by a larger organizational container. For example, in Haier, one would find the Organization (Haier Group) controlling directly many subsidiaries that in turn are organized as above, and also many fields and sub-fields that in the case of Haier describe the operations that pertain to a specific area of interest (e.g.: Food, Smart Home…).

On top of the artifacts introduced, two more need to be specified. The first is the easiest, and we’re talking about a “black box”. The black box represents an external party, that is defined by its Identity and — potentially — Reputation but doesn’t use the same “organizational grammar” we’ve been describing so far. A black box can still be engaged with a standardized and simple bid-order contract (which is effectively an abstraction of a basic trade contract overall).

The VAM (Micro-Enterprise incubation) Contract

The last one is a very important artifact and it’s called a VAM Contract. VAM – which stands for Value Adjustment Mechanism – is a mix between an investor term sheet, a contract and a corporate budgeting statement. VAM contracts are signed between ME prospect owners (employees) and the organizations (or its fractal divisions). VAM contracts have historically been frequent in Asia and are to be seen as qualitative term sheets that are based on the idea of having an investment contract based on qualitative outcomes that unlock certain opportunities for the investees (essentially often access to more equity).

VAMs normally cover the constitution phase of a Micro-Enterprise and the subsequent development periods (yearly reviews) and are used to set objectives for a new Micro-Enterprise and regulate the investments that the organization makes into creating one.

VAM contracts contain 5 key elements:

- basic information of the micro-enterprise such as who are the employee founders/leaders;

- detailed information about the ME aim, and leading goals;

- a description of how the ME will reach the goals;

- the needed resources for the ME to pursue its startup, including capital;

- the inflection points that will represent the moment the startup process is ended.

- information about the upsides for the employees in terms of employee bonuses, accessing profits, and accessing equity.

Clearly, VAM contracts best apply to 3EOs that adopt Positive P&L as the defining health function of the Micro-Enterprise and may need tuning to be fully applicable to contexts where other metrics are adopted.

Patterns that resemble the VAM and EMC are also existing in other organizations. As an example, Amazon has transcended the traditional budgeting process (that normally looks into allocating funds to units) through its OP1-OP2 process (see here and here). The OP1 process that is largely responsible for capital allocation is based on:

- single teams providing in June their objectives for the year in a carefully crafted six-pages document (an equivalent of the yearly negotiation of the VAM);

- plans are collated at every organizational layer and looked into in a holistic manner (as in an EMC);

- leadership (starting from the CEO) decides how to distribute the funds.

The process is thus similar to what a combination of VAMs and EMC do (focusing on customer outcomes, systemically engaging many units presenting a holistic view) but less dynamic, and with a more consistent focus on the objective dictated by the leadership: in a nutshell, we can say that Amazon is inclined to accept slightly less creative entropy in its continuous renewal process than Haier is inclined to accept.

The formulation of this mix of dynamic contracts, and targets may be emerging as an evolution of the traditional stable organization structure.

A Recap on common artifacts

As a recap, here’s the full list of EEEO/3EO artifacts:

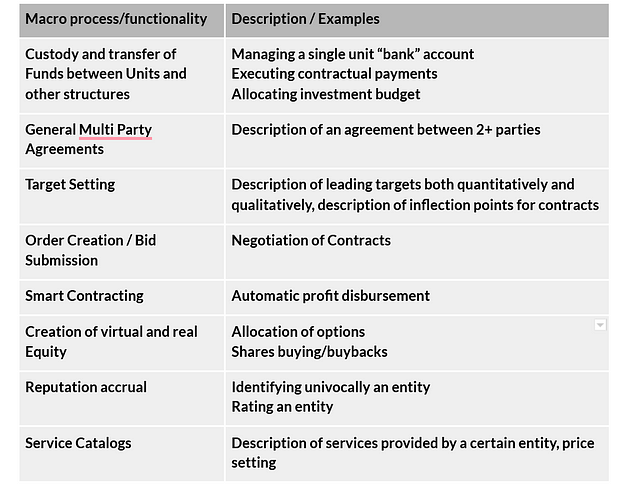

To power properly those artifacts the following list of processes will need to be executed:

Next Steps: Building a software ecosystem on a shared model?

If we agree that a common logic substrate, a shared grammar, like this is emerging as a common organizational framework, it becomes natural to think about how we could build technologies that would help players that are interested in adopting such an organizational structure.

More in details such a technological solution would:

- make it easier for organizations to adopt these organizational structures;

- make it possible for organizations to interact with each other through shared layers and shared protocols (as an example, letting EMC-like contracts to be created across organizations, temporarily move units across organizational boundaries, etc…

- possibly enable a transition towards a world of ecosystemic “organizing” vs a world of bounded and competitive “organizations”.

More information about our next steps in the creation of the software ecosystem will come soon in following updates.

To stay tuned and express your interest on the project, please check out this form.