The Four Archetypes of Platform Organizations

Decoupling and coherence as the twin engines of strategy

Simone Cicero

In our work with organizations aiming to improve their operating models for growth and adaptability, we’ve been working with organizations that look nothing alike on the surface.

Industrial manufacturers with diverse product portfolios, digital players chasing “super-app” ambitions, or radically open B2B service platforms face the same structural tension. Markets demand multiplicity: more segments, bundles, business models, and ecosystem plays, while, on the other hand, customers also seek consistency and trust.

Modern organizations must balance variety in offerings and coherence in customer experience, alternating them in their strategy.

The core idea is that you’ve to run a Portfolio and a Platform strategy, balancing these approaches based on market dynamics and organizational goals.

Why Having Both: a Portfolio Strategy and a Platform Strategy

When we say “portfolio strategy,” we mean pursuing diversification through different business units, products, or market segments, each operating with relative autonomy. This allows organizations to create optionality (by keeping multiple paths available), spread risk, and capture various market opportunities, also enabling employees to express their creativity.

The key force behind a portfolio strategy is Decoupling. Decoupling reduces or standardizes dependency interfaces and allows the organization to create options. When product teams can evolve their roadmaps independently and when technical and service components are modular, the organization can run several bets in parallel and reallocate attention and capital toward what pulls customers. That’s the portfolio engine: disciplined exploration without freezing the system.

Coherence helps customers turn their interactions with the brand into structured, impactful outcomes. It operates not through uniformity between services, but ensuring operational compatibility, shared underlying meaning, and ontologies between portfolio elements.

A “platform strategy” drives coherence across a complex offering: it focuses on creating shared capabilities, data, and infrastructure for seamless integration and consistent experiences. A platform strategy allows the organization to leverage network effects by creating virtuous cycles/flywheels targeting multiple stakeholders, including key end-users and third parties.

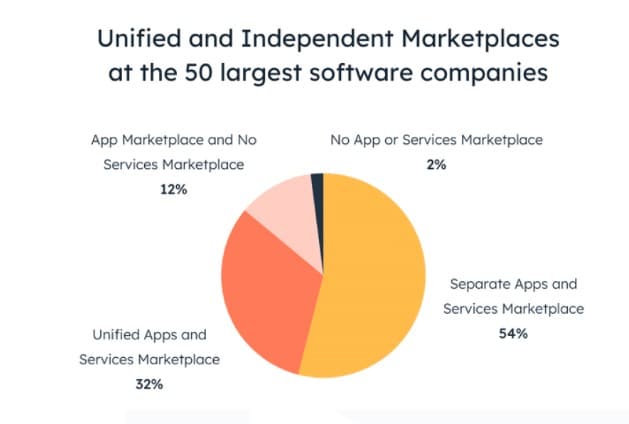

In B2B settings, partners can add value to an offering by complementing a company’s value proposition through compatible extensions, service integrations, local deployment, and more. The concept of a partner ecosystem is well-known, particularly in software-centric B2B (think of Salesforce’s AppExchange). As of 2024, the State of Platforms Report, essentially everyone doing Business SaaS has a platform strategy involving third parties.

Structured initiatives to coalesce partner ecosystems are emerging in complex industries like manufacturing or electronics (think Siemens Xcelerator marketplace, for example), and intentionality is essential for your strategy’s success.

A platform backbone—providing consistent identity, data, semantics, policy and compliance, observability, composability—enables the organization to “rebundle” its offerings, ensuring the experiences compose cleanly for the customer and combine with third-party offerings, creating innovative vertical experiences, allowing each customer to enjoy a fully customized experience.

The idea is simple: decouple (portfolio) to explore, recouple (platform) to scale.

The four archetypes (a simple 2×2)

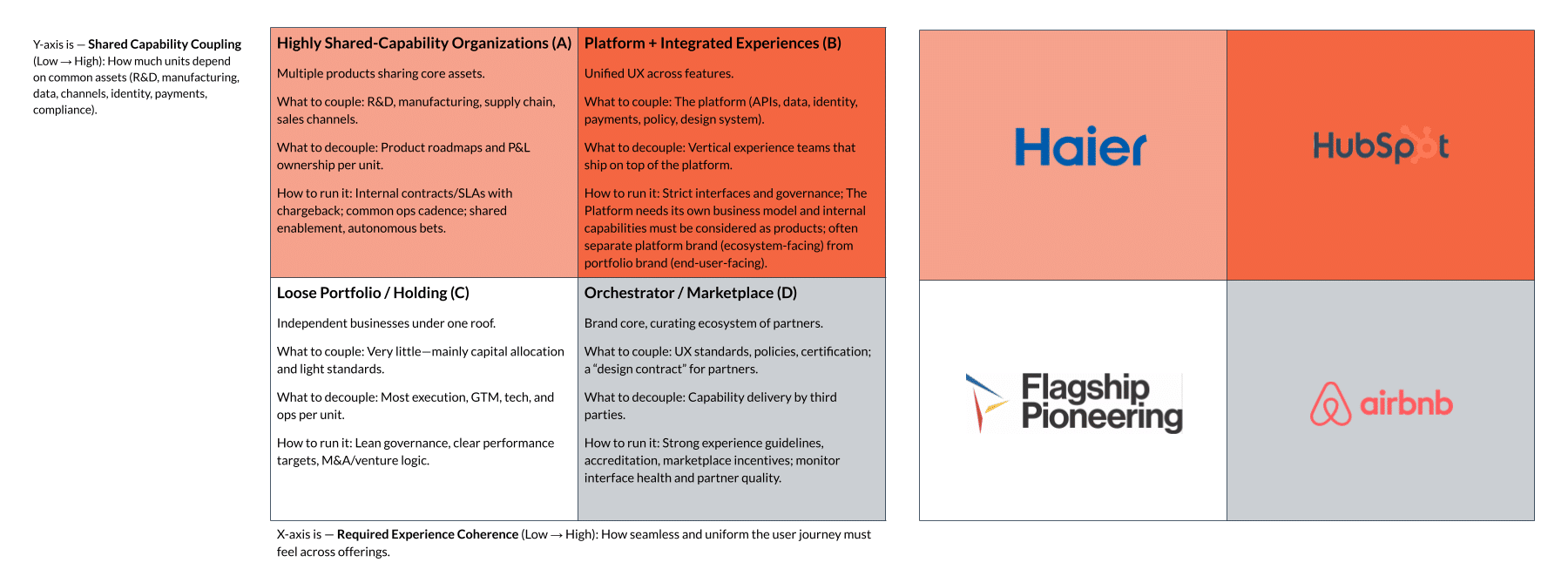

Not every company needs the same approach to balance these two motions. The landing point depends on two aspects: the coherence required in the customer experience and the coupling among shared capabilities. For example, a company aiming for a “super app” experience has a high bar in customer experience coherence. In contrast, an organization with a high manufacturing footprint typically has high coupling among manufacturing, logistics, and often R&D.

If we put Required Experience Coherence on the horizontal axis and Shared Capability Coupling on the vertical axis, we have a useful 2×2 matrix to assess and strategize our company’s position: the map doesn’t prescribe one correct model, but clarifies trade-offs.

1) Highly Shared-Capability Organizations (A)

Experience coherence is moderate; the portfolio spans verticals, but the coupling of core capabilities is high because they are typically capital-intensive. Think portfolios where units share heavy assets—R&D, manufacturing, supply chain, channels. You want to keep roadmaps reasonably autonomous (and product lines accountable to their customers) while using internal contracts for accessing capabilities and shared technology, ideally favoring recontribution of innovations to the shared core. When this works, shared services and technology platforms accelerate time-to-market; when it fails, central functions dictate roadmaps, and autonomy becomes a formality along with adaptability. The primary risk is losing perceived neutrality within the ecosystem if the core competes in too broad a range of verticals.

A good example is Haier. They’ve inspired and collaborated on our 3EO Toolkit for the Platform Organization. Haier has transformed from a traditional appliance manufacturer into a platform-based ecosystem organization. They maintain strong shared capabilities in manufacturing and R&D (for example, their “refrigeration platform” or “washing platform”) while allowing individual micro-enterprises to operate autonomously. Their model enables rapid innovation and market responsiveness across diverse product lines, from smart homes to IoT solutions, all while leveraging common core competencies. This balance between decentralized decision-making and centralized capabilities has become a blueprint for industrial transformation.

2) Platform + Integrated Experiences (B)

In this context, the experience coherence and capability coupling required are extremely high, typical in software-as-a-service platforms serving complex business processes. A robust shared platform (design system, data model, policies) underpins a seamless user experience across features. Vertical teams can be relatively autonomous, but business outcomes and growth objectives need to be distributed with a systemic view. The North Star is the whole product experience, not single unit optimization.

Example: A good example is HubSpot. HubSpot balances integrated user experiences across its marketing, sales, service, CMS, and operations hubs while maintaining a unified platform architecture. Their design system, shared data model, and workflow model, along with a consistent API approach, enable seamless transitions between products, including third-party ones. Third-party developers can extend functionality through their App Marketplace, yet the core experience remains cohesive. This model demonstrates how companies can maintain high experience coherence while supporting ecosystem innovation through standardized platform capabilities.

3) Loose Portfolio / Holding (C)

Experience coherence is low here because all verticals operate in their own business context; shared capability coupling is also low. The organization may have shared IP or labs, but doesn’t need to orchestrate access to centralized capabilities with minimal bandwidth. Businesses operate independently with minimal governance, and capital allocation becomes the primary strategy: choosing where to invest is the mechanism of strategic coherence. This is a legitimate strategy when synergies are weak or when you want diversified exposure. The risk is having a shallow thesis, leading to the organization spreading itself too thin; the remedy is a clear strategic direction in business sectors where the organization can leverage additional value drivers, such as shared distribution or a strong brand, and a focus on results.

A notable example is Flagship Pioneering, a hybrid venture creation and investment firm managing a diverse portfolio of biotech companies aiming to be “enabling platforms.” They have a process to incubate new ventures that operate independently, with their own management and go-to-market strategy. While sharing some foundational insights and methodologies, companies like Moderna and Indigo Agriculture pursue distinct markets with minimal overlap. This approach enables flexibility while maintaining a focus on breakthrough innovations in life sciences and sustainability.

4) Orchestrator / Marketplace (D)

In this quadrant, experience coherence is high, but capability coupling is low within the firm because partners deliver most of the capability and inventory, while the organization provides enabling constraints and compliance. The core owns the brand trust, standards, policies, identity, payments, and experience guardrails. Partners create the variety; the orchestrator guarantees a consistent journey and resolves disputes.

Example: A notable example is Airbnb. Airbnb provides a standardized platform where hosts can list properties and guests can book accommodations, maintaining strict quality standards and user experience consistency, including customer support. The company, despite not owning properties, focuses on creating trust through verified reviews, secure payments, and standardized communication protocols.

Organizational mirroring: what must exist inside

If your company’s outside value proposition is a mix of a Portfolio and Platform strategy, the inside needs to be structured, architected, resourced, and managed to mirror and execute it.

To function effectively, a portfolio engine must comprise entrepreneurial units and effective capital allocation. Depending on your archetype, nodes can have real P&L and roadmap ownership, be bound by explicit contracts for shared services, or be responsible for specific business outcomes. These units are closer to markets and GTM channels, and carry the burden of choice: what to build, bundle, or stop. From a brand architecture standpoint, the stronger the portfolio strategy, the more the brands need flexibility. When the platform engine is key, the organization should avoid direct brand competition for its end-user product brands to avoid chilling partner adoption.

In companies where experience coherence adds value, the platform engine needs to be a standalone product with Product Management leadership. It owns APIs and SDKs, data contracts, identity, policy, risk, payments, design tokens, and governance for healthy interfaces. In such contexts, Third parties/Developer Relations—internal and external—shouldn’t be an afterthought.

All the archetypes above need to juggle three major capabilities:

- Autonomy in delivering customer-facing value

- A Platform capability to support internal/external value providers and third parties on a shared set of modules and services, and generate compounding value through scale and network effects.

- A capital allocation capacity to continuously seed innovation.

Why does knowing your quadrant matter?

Misidentifying the quadrant is one of the most expensive mistakes we see. A company wanting to run as an integrated platform that behaves like a loose holding, fragments UX, and gets bypassed by teams.

An organization that wants to tackle diversity of opportunity but strangles teams with adherence to standards, platform services, and reliance on internal peers will never deliver, as it competes with competitors with fewer execution constraints.

Understand that the choice isn’t always yours: the market context and competitive dynamics often dictate your organization’s quadrant. Markets with strong network effects evolve towards platform models, whereas fragmented markets with diverse customer needs and legacy third-party presence may require a portfolio approach. The key is recognizing these forces early and aligning your organizational structure, processes, and capabilities accordingly.

A quick self-check helps: what level of experience coherence do customers notice and value; which capabilities to share; how much perceived neutrality to attract partners; and how much offer variance to generate in the next planning cycles. If these answers are fuzzy, conflicting playbooks will surface inside the same company.

Closing

A modern organization shouldn’t have to choose between variety and order. They should design a cycle that expands optionality through decoupling and converts it into coherent experiences through a platform backbone. The four archetypes make the choice explicit for each business; the organizational mirror turns it into practice. When the quadrant is clear and the mirror is in place, conversations get simpler, priorities sharper, and trade-offs intentional.