How can Venture Capital and Platform Organization Paradigms Reinforce Each Other?

This article explores how the venture capital approach is a necessary skill Platform Organizations should learn and apply to leverage the internal innovation, and on the other hand how the fragmentation and complexity of a Venture Capital firm can benefit from adopting Platform Organization structures.

Luca Ruggeri

This blog extends the main concepts discussed live in the Webinar Venture Builders and Platform Organization, produced in the Summer of Platforms series.

In today’s dynamic corporate innovation landscape, Platform Organizations have become instrumental in fostering entrepreneurship from within, blending venture capital and venture-building elements to empower intrapreneurs with the resources and agility typical of startups. These organizations, also known as Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Enabling Organizations (3EOs), focus on decentralizing traditional corporate structures into autonomous units, driving innovation and efficiency. By integrating startup-like agility with corporate resources, Platform Organizations accelerate internal innovation and enhance collaboration with external startups. This blog post explores the intersection of venture capital dynamics and Platform Organizations, emphasizing how both can benefit from cross-pollination and highlights the potential for companies to adopt this adaptive model for sustained growth and competitive advantage in rapidly evolving markets.

Introduction

Platform Organizations have emerged as a pivotal model for fostering entrepreneurial ventures from within in the rapidly evolving corporate innovation landscape. These organizations, acting as both venture capital firms and venture builders, provide intrapreneurs with the resources and support typically found in the startup ecosystem. By offering capital, capabilities, and extensive networking opportunities, Platform Organizations enable the creation of new offerings with the agility and dynamism of startups. This approach accelerates internal innovation and facilitates a seamless collaboration – in a progressive evolution – with external startups. The interplay between traditional venture capital practices and the adaptive strategies of Platform Organizations holds immense potential for driving sustained growth and innovation in today’s competitive market.

What is a 3EO Platform Organization?

Before enunciating the central thesis connecting the Venture Capital ecosystem with corporations, let’s briefly describe the main elements of Platform Organizations. Eager readers can find more details here Ecosystem-Driven Organizations: Shared Market Maps, Forcing Functions and Investing into Small Units. – Boundaryless and here How To Structure Units and Teams in a Platform Organization – Boundaryless.

A 3EO (Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Enabling Organization), or Platform Organization, fosters innovation and efficiency by putting self-responsibility, autonomy, and entrepreneurial development at the center. It supports internal entrepreneurs (intrapreneurs) through a combination of resources, strategic guidance, and a supportive network, allowing them to operate with the agility of startups. The core principle of a 3EO is to break down traditional hierarchical structures into smaller, autonomous units that can rapidly respond to market opportunities and challenges and dynamically interact through transparent interfaces, contracts, and value-driven interactions.

Primary Artifacts of 3EO Platform Organizations

In practice, the Platform Organization is implemented through a series of artifacts, here described:

- Micro-Enterprises (MEs)

- Micro-enterprises are self-managed, small units within the organization that function like independent startups or product/solution owners. They are empowered to make decisions, manage their own P&L, and be held accountable for their performance. This autonomy enables them to innovate quickly and effectively from a customer / value-driven perspective.

- Shared Service Platforms (SSPs)

- Shared Service Platforms provide essential services and resources to Micro-Enterprises, ensuring they have the support needed to succeed. These services include HR, legal, finance, IT, and more, allowing MEs to focus on their core activities without getting bogged down by administrative tasks.

- Value Adjustment Mechanisms (VAMs)

- VAMs are contractual agreements that define the relationship between different units within the organization. They specify the objectives, investment requirements, and expected returns, ensuring alignment and accountability. VAMs help manage the flow of resources and investments, fostering a results-oriented culture.

- Ecosystem Micro-Communities (EMCs)

- EMCs facilitate collaboration between different units and external partners. These communities are formed around shared goals or market opportunities, leveraging collective expertise and resources to innovate and create value. EMCs enable fluid interaction between internal and external stakeholders, breaking down traditional organizational silos.

- Industry Platforms (IPs)

- Artifacts adopted to distribute an organization’s investment capacity into business sectors. Each industry platform is a “sub-organization,” using Shared Services Platforms for support services (typically HR, IT, Legal, and Finance…) but managing investment cycles autonomously, and in some cases, also sensing markets and spotting opportunities, then exploited by the incubated MEs.

Implementing 3EO Principles

Transitioning to a 3EO model involves significant cultural and procedural changes, as you read in the Manifesto for the Platform Organization – Boundaryless. It requires fostering a culture of entrepreneurship, providing clear strategic direction while maintaining flexibility, and implementing mechanisms that support self-management and inter-unit collaboration. The ultimate goal is to create an environment where internal and external innovation can thrive seamlessly, blurring the lines between the organization and its ecosystem.

Among all the key principles described in the Manifesto, the most relevant ones for this thesis are:

Enabling Constraints and Forcing Functions

- Enabling constraints are designed to guide rather than control the organization. These constraints help balance autonomy and coherence, ensuring that the various units within the organization can innovate independently while aligning with the overall strategic goals. Forcing functions, such as positive P&L requirements or specific KPIs, are adopted to drive performance and accountability within these autonomous units.

Centralized Strategy with Distributed Execution

- While the Platform Org model promotes autonomy, some centralization is needed, particularly in strategy formulation and resource allocation. This ensures that the organization’s overall objectives are met while allowing individual units to operate with significant freedom. The central strategy team or dynamic process internalizes insights from the market and ecosystem, guiding investment and prioritization decisions.

Continuous Market and Portfolio Analysis

- A critical aspect of the 3EO model is the continuous analysis of the market and the organization’s portfolio. This involves identifying gaps, synergies, and opportunities within the ecosystem, enabling the organization to adapt and evolve its offerings in response to changing market dynamics. Tools such as Wardley Mapping and the Platform Design Toolkit facilitate this analysis.

Cultural and Procedural Innovations

- Transitioning to a 3EO model involves significant cultural and procedural changes. This includes fostering a culture of entrepreneurship, providing clear strategic direction while maintaining flexibility, and implementing mechanisms that support self-management and inter-unit collaboration. The ultimate goal is to create an environment where internal and external innovation can thrive seamlessly, blurring the lines between the organization and its ecosystem.

By embracing these principles, companies can unlock new levels of agility and innovation, better positioning themselves to compete in dynamic markets. This approach not only supports the development of internal ventures but also enables collaboration with external startups, creating a robust, ecosystem-driven innovation model.

The Development Thesis

Summing up all the key learnings, we see that Platform Organizations and Venture Capital (ecosystem, practices, development model, and firm perspective) have meaningful overlaps and cross-pollination potential.

In particular, we see that:

- Platform Organizations can solve many innovation/efficiency/growth/impact issues or missed opportunities by emulating the dynamics of venture-startup ecosystems within their inside;

- Platform Organizations can support the dynamics of the Venture Capital ecosystem by being more ready to interact with startups and provide growth potential or co-fund them, or be part of their exit strategy;

- On the other hand, Venture Capital firms (and all of their flavours, like Venture Builders, Venture Studios, Distributed/Collective/Open Venture Capital networks, etc.) can also benefit from the adoption of Platform Orgs’ crystal clear and scalable dynamics.

Let’s describe how the two perspectives can influence and benefit each other.

Venture Capital for the Platform Organization

We can simplify how venture–startup ecosystem best practices can improve the dynamics of Platform Organizations by identifying the main challenges such an organization is required to deal with in the journey to innovate, build more valuable products, or extend the existing ones to grow.

Venture Capital firms – with the primary intent of having returns in the medium-long period – adopt a derisking approach based on the power law, i.e., they invest in a large number of ventures, the “portfolio companies” (the “startups” in a friendly definition), knowing that only very few of them will survive to the complexity of markets. Indeed, the few champions will hopefully be large enough (as a return opportunity) to repay everyone who worked for the Venture capital firm and, of course, grant exceptional returns to the primary VC investors, the so-called LPs – Limited Partners.

To maximize the chances of meaningful returns, the VC also has to be capable of detecting the key trends in their domain industries to avoid temporary bubbles or over-hyped solutions and/or actively try to influence the product side and the org development side thanks to networking with domain experts, industry leaders, access to empowering technologies and research outputs.

On the other hand, having many portfolio companies competing in the real market reduces the “pressure” on the VC, which can only be partly responsible for the startup’s success or failure; most of this responsibility is in the startup itself.

If you compare the typical – or promised – advantages for a corporation that wants to adopt an open innovation paradigm, you easily read that they are:

- Access to external knowledge, ideas, expertise

- Increase the speed to market and/or the product innovation cycles and the adoption of state-of-the-art technology

- Keep risk and costs under control, for instance, keeping projects and experiments small, well framed, and with a clear and narrow purpose, or splitting complex projects or objectives into agile experiments, easier to validate and measure

Venture Capital firms focus precisely on the same goals from a different perspective. Instead of integrating products and startups, they keep them independent. They focus on collecting results and value sharing through P&L (IRR). They establish interfaces to transparently define conditions and outputs in a milestone roadmap (term sheets). They support profitable innovation at scale and achieve massive impact on society through the solutions developed, with a global perspective.

Platform Organizations aim to achieve similar objectives, but in order to scale this approach and make it a cultural habit inside the organization, they have to learn the VC best practices.

So, VAM can learn from Term Sheets. Micro Enterprises (equivalent to the portfolio companies in the metaphor) need investments, capabilities, assets, networks, and SSPs to operate better and control costs and coherence. VCs’ due diligence processes, together with their capability to read industry trends and spot opportunities, should be deeply integrated into Platform Org best practices and key processes. This is somehow what is already happening in the Industry Platforms artifacts, where the organization constrains the vertical contexts or industries to invest resources – budget and assets or capabilities – to gradually gain confidence in the mindset change from builders, to investors. The thesis expressed here, is that the VC paradigm has to be gradually scaled to the entire organization, expanding what is done in the IP – also with an IP of IPs perspective -.

The VC approach can also be beneficial in solving some of the typical issues connected with (open) innovation practices in corporations:

- Protection of intellectual property or confidentiality – attached to the portfolio company / ME and not disclosed or integrated company-wide

- Avoid long and complex negotiations by introducing “standards” (SAFEs, PACTs, Contracts, etc.)

- Needs for cultural change. Reducing the team sizes into small product startups the impact and scale is reduced, with a more controllable output

- Integration challenges and/or complex project management are completely waived by reducing all the interactions to contracting, or by forcing the interactions through clear interfaces only (APIs for the tech side, processes for the workflows)

In essence, we believe that every organization that wants to be competitive in this century should become a Platform Organization, since it’s the most adaptive and composable structure that can integrate one of the most successful innovation and exponential growth models so far: the venture capital one. Thus, if a Platform Org behaves as a Venture Capital firm, it can evolve from a hierarchical innovation-by-imposition and not efficient (try to measure the ROI on innovation in such a scheme!) into a Venture Builder (focused mainly on its inside) and ultimately become a Venture Capital, where there’s little or no difference if the “new products or innovations” are incubated from the inside or the outside of the organization…

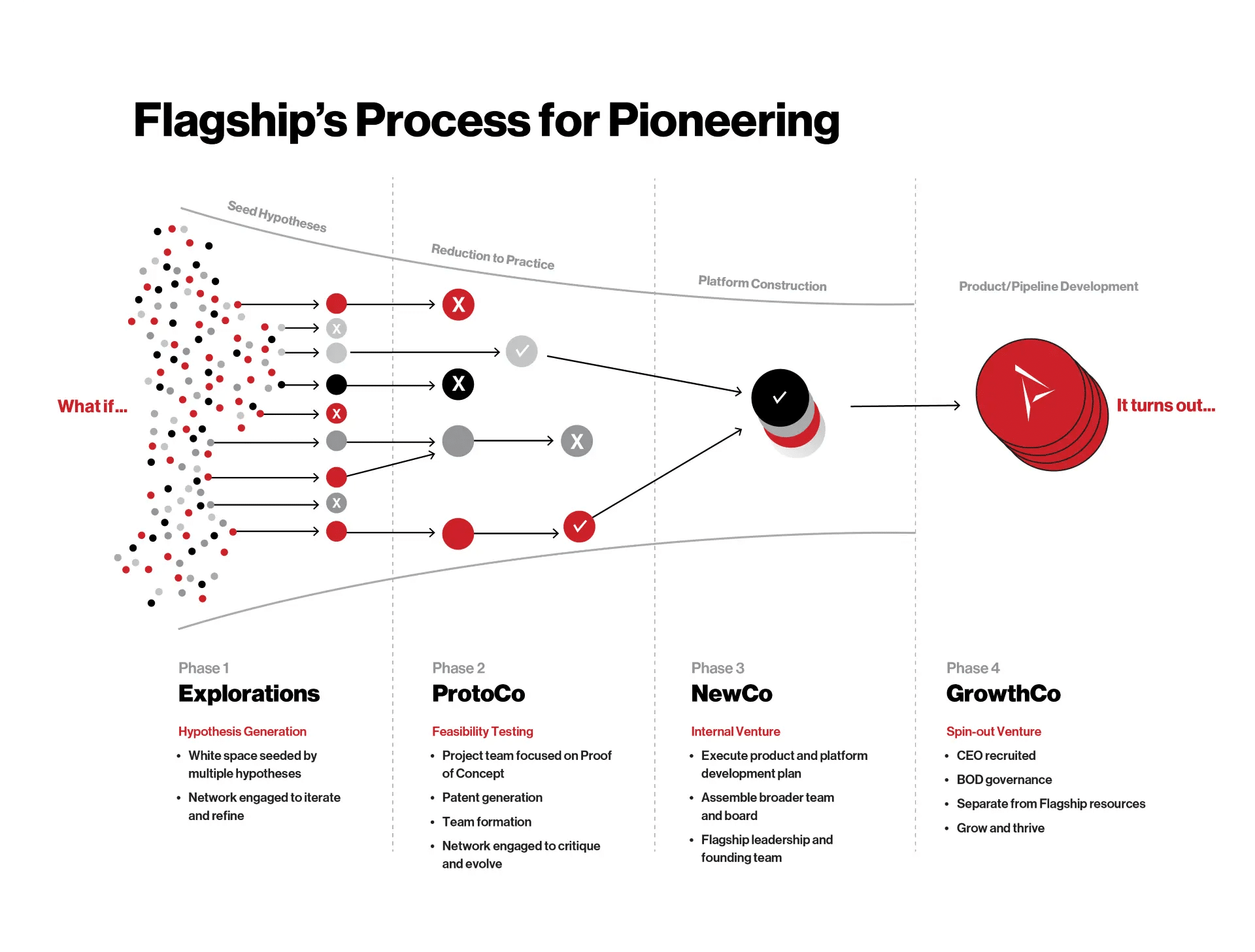

There are real examples of this approach. One of the most relevant is Flagship Pioneering’s with its “Process”: an approach that, by combining venture funding with shared enabling services, allows them to create 10 new “ProtoCos” (prototype companies) every year that aim at becoming platforms that enable product innovations in a key vertical space. This process helped Flagship Pioneering create an ecosystem of forty companies (started as ProtoCOs) to help the organization thrive Navigating the Polycrisis. If you can’t associate the name of Flagship Pioneering with memorable results, among their companies, Moderna became pretty famous in 2020. And they are scoring continuous great results, ranking regularly in the top 3 most innovative companies in the world according to Fast Company.

Platform Organization for Venture Capital

On the other hand, Venture Capital firms are complex organizations with very diversified sizes, industries, approaches, and very fragmented expertise and network reach.

If we just list all the roles, key outputs, and processes executed by a Venture Capital firm, we have a very long list of fragmented elements, often “reinventing the wheel at every iteration with funds and portfolio companies”:

Roles and duties:

- General Partners (GP) conduct due diligence, negotiate terms, sit on the boards of portfolio companies, and provide strategic guidance to these companies. They have a significant influence on the firm’s direction and success.

- Limited Partners (LP) invest in the VC fund and typically do not have a direct role in investment decisions or portfolio management. Their primary concern is the return on their investment.

- Managing Partners (MP) manage the firm’s administrative functions, ensure compliance with regulations, and may also actively participate in investment decisions and portfolio management.

- Principals conduct initial due diligence, assist in negotiations, monitor portfolio companies, and help in strategic planning. They often take the lead on smaller deals or co-investments

- Venture Partners can be industry experts or connectors who help to source the best deals or can help analyze profound aspects of the deals and startup solutions and products.

- Associates handle much of the groundwork in deal sourcing and due diligence. They analyze financial statements, market conditions, and business models and prepare investment memos for the senior team.

- Analysts perform market research, financial analysis, and competitive analysis. They help build financial models and prepare reports that inform investment decisions.

- Mentors or Advisors offer insights on industry trends, introduce potential deals, and provide mentorship to startup founders.

- Operating Partners assist portfolio companies with scaling operations, strategic planning, and operational improvements. Their role is to ensure that the companies achieve their growth potential.

- Backoffice Staff handle the firm’s day-to-day operations, compliance, investor relations, and financial reporting. They ensure the smooth functioning of the firm’s internal processes.

Fund Structure and macro-objectives of the VC Firm

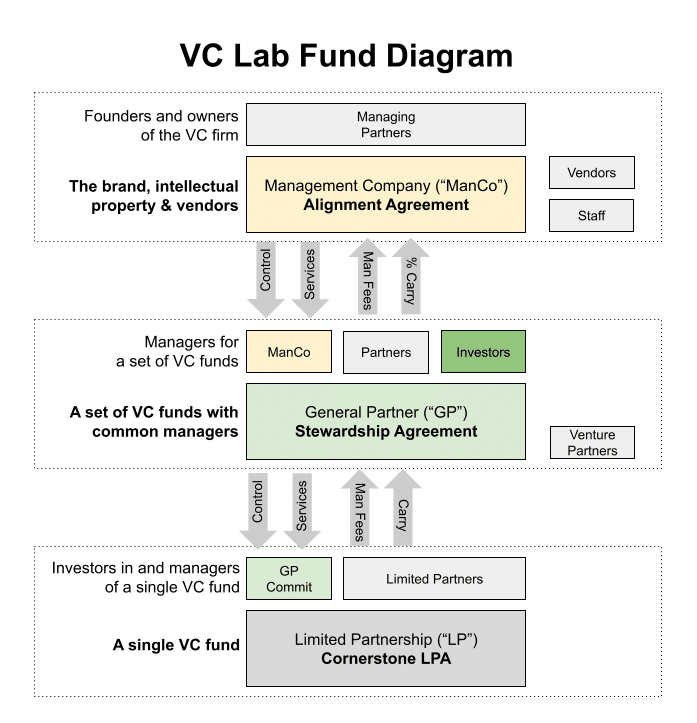

Mainly the VC firm is split into two main structures:

- Venture Capital Funds: The capital raised from LPs is pooled into funds. Each fund typically has a lifespan of 10 years, with an investment period of about 3-5 years and a subsequent period for managing and exiting investments. The fund also manages the portfolio of companies, providing ongoing support and eventually seeking exits through IPOs, mergers, or acquisitions to generate returns for LPs.

- Management Company: The firm, administrated by the managing partner, is responsible for all the compliance and legal aspects of fundraising, including one and then multiple funds, to secure returns for all the stakeholders. It is also responsible for the branding and reputation, networking and relationships with institutions, industry representatives, and so on

In a typical VC, a single management company launches a new fund sequentially, every 3-4 years. So, after some iterations, the management complexity can be really huge: many GPs, many LPs, aggregated in different shapes and with different strengths, and many portfolio companies (i.e., the startups where the funds are invested).

Structure of a typical VC Firm with several funds and partnerships, taken from a great source about Venture Capital, VCLab.

In addition, there are some repeating actions (contracting, sourcing, protecting IP and patenting, legal support, accounting, and events management, just to mention the most common ones) that every VC does – and typically, reinventing the wheel every time – with a poor economy of scale, and poor capability to learn from market-driven lessons, and typically with costs that can have a significant impact on the expected returns to the LPs. According to standard practices, these recurring activities can cost 2-3% of the entire fund size every year. Our astute reader, familiar with the optimization offered by Platform Org structures, sees that these activities are ready for standardization and efficiency at scale.

The fund(s) also execute continuously a process that is composed of a sequence of milestones, such as:

- Deal Sourcing: Identifying potential investment opportunities through networks, events, and direct outreach.

- Due Diligence: Thoroughly evaluating the business model, market opportunity, financial health, and management team of potential investments.

- Investment Committee: A group within the firm, typically comprising GPs, that reviews potential deals and makes final investment decisions.

- Funding and accounting: Delivering the investments to the portfolio company

- Portfolio Support: Actively managing and supporting portfolio companies to help them grow and succeed.

- Exit Strategy: Planning and executing exits to realize returns, including IPOs, acquisitions, or secondary sales.

Despite some well-established best practices in the VC ecosystem for the above steps, every fund comprises different actors. Thus, the processes are non-standard: here, it’s the space for uniqueness among different funds and VC firms, even in the same industry vertical.

What Platform Organization elements are significant for VC?

The focused reader has already imagined what elements VC firms can withdraw from the large pool of practices offered by the Platform Organization. Here are some examples:

- VC Funds can be considered MEs, having their “P&L” measured by the IRR. Large funds, or Venture/Startup Studio funds, might be considered as Industry Platforms as well.

- Functions (operating partners, mentors, consultants, etc.) can be other Node MEs or SSPs, depending on the uniqueness of their value or needs for standardization and efficiency.

- An EMC contract can be established between Funds MEs, Functions MEs, and the ManCo.

- Inside the Fund, a VAM can be established as a “term sheet” better artifact, since it can include not only funds but all the other services offered.

- Enabling platforms are SSPs and can also be scaled to serve multiple internal clients, like HR, Legal, Accounting, Marketing, Market Analysis, Financial Planning, Relationships with Investors, not to mention cases where the Fund is also providing enabling tech (a protocol, a tech stack, a platform to measure results, etc.)

- The ManCo or the Fund can use EMC to partner with other industry leaders, such as cloud computing solutions, acceleration program providers, training facilities, and so on, establishing data-driven and objective profit-sharing mechanisms with all the actors.

The level of standardization and efficiency obtained by developing these elements and interfaces, as well as the guiding processes, can be studied from one specific case but then become industry-wide, increasing efficiency and saving costs: it’s easier to think of changing the famous 20-2 model, where the management “fee” can be much lower than the 2%, or where the profit sharing schemes can become sophisticated and progressive, in line with the actual market results and adopting the same liquidity events in the portfolio companies as triggers for the distribution of value to all the active participants.

Introducing a provoking thought, let’s also consider this additional case: today, we all see the VC industry becoming increasingly fragmented, not to say more commoditized. VCs are appearing (or disappearing) continuously, of a smaller and smaller size, where the value given to portfolio companies is not only the money for equity but more and more the vertical expertise from the industry that the specific VC can bring. There are growing experiments of Collective VC, Open VC, or distributed VCs where the ecosystem itself aggregates investors into a syndicate-alike shape (replicated at a local level or a vertical industry level) but where the supporting functions can be in common and every stakeholder needs a transparent and objective sharing of the results. Or, having a straightforward interface, scope, and contracts where people – professionals, entrepreneurs, ambassadors – can have their role officialized and regulated transparently, increasing the willingness to contribute to the ecosystem development actively.

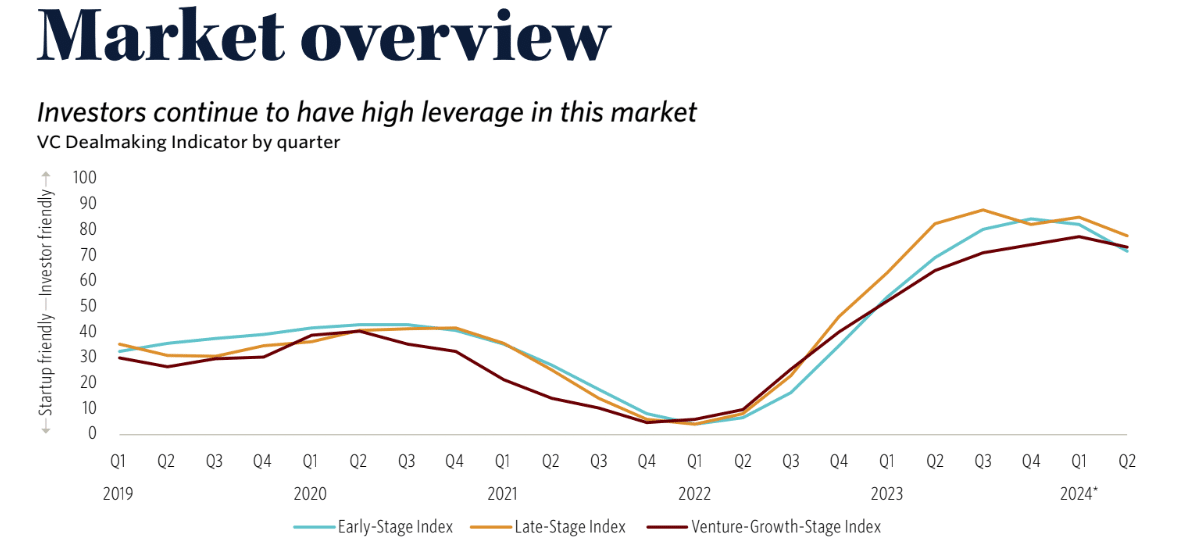

And, fresh data coming from the NVCA – National VC Association in the US – in their annual report available at this link, show how the investors – and here, let’s include the Corporate Venture Capital investments and the role of large organizations – still have a strong leverage in the innovation ecosystem.

Conclusions

This article is to be interpreted as a first stub in the series Venture Builders and Platform Organizations, connecting the dots between the venture capital ecosystem and the prominent role that adaptive organizations can have in the products and solutions development ecosystem, including the relationship between startups and internal innovation.

In future blog posts we will explore the role of open innovation practices in the Platform Organizations, how the open market perspective of VC can support the procurement of innovative and state of the art solutions from Platform Organizations, and how the VC fragmented ecosystem can benefit from a shallow adaptive structure. Stay tuned and don’t forget to share your thoughts with us.