Self-Organizing Around Production Chains. Regenerative Economics, Beyond Efficiency and Growth

In this article, we offer an initial reflection on tackling regeneration from a specific perspective, that of, context-based, self-organization around production chains. We also introduce a theoretical backing of the reasons why such a small-scale, emergent way to produce a response to degeneration could make sense, and also outline the major limitations that slow down an organic adoption of such an approach.

Simone Cicero

Abstract

In the quest for the reinvention of economic systems, the word regeneration has been used and abused. Multiple approaches have emerged to tackle the complexity of the challenge of reinventing economic models – and production in particular – in a way that creates benefits instead of generating negative externalities. Many voices have grappled with the problem, looking at the issue from different angles. At Boundaryless we’ve been also part of the process: in June 2021 we co-hosted the Regenerative Platforms Sense-Making Event, as we kickstarted the Regenerative Platforms Alliance together with several partners and members of our network. In this article, we try to offer an initial reflection on tackling regeneration from a specific perspective, that of, context-based, self-organization around production chains. In the piece, we also introduce a theoretical backing of the reasons why such a small-scale, emergent way to produce a response to degeneration could make sense, and also outline the major limitations that slow down an organic adoption of such an approach.

Regeneration: a lacking common ground

In many cases, the attempt to research the questions around regeneration has produced principles of regenerative economics. Our Boundaryless teammate Lucia Hernandez – that joined us on the Boundaryless Conversations Podcast to share some of her preliminary findings – recently scanned the regeneration discourse and came up with four key recurring principles: interconnectedness, emergence, evolutionary nature, and holism that seem to characterize regenerative approaches. Before that, in 2020, a key institution in design such as RSA came out with their Regenerative Futures identifying 8 principles pointing out a regenerative model of an economy based on being inclusive and multi-perspectival, embedded in place and aware of the nested nature of health and wellbeing (something we discussed previously with regenerative thinking legend Daniel Wahl on the podcast), circular in nature, emergent, hopeful and – at the end of the day – rooted in different and new personal priorities and mindsets.

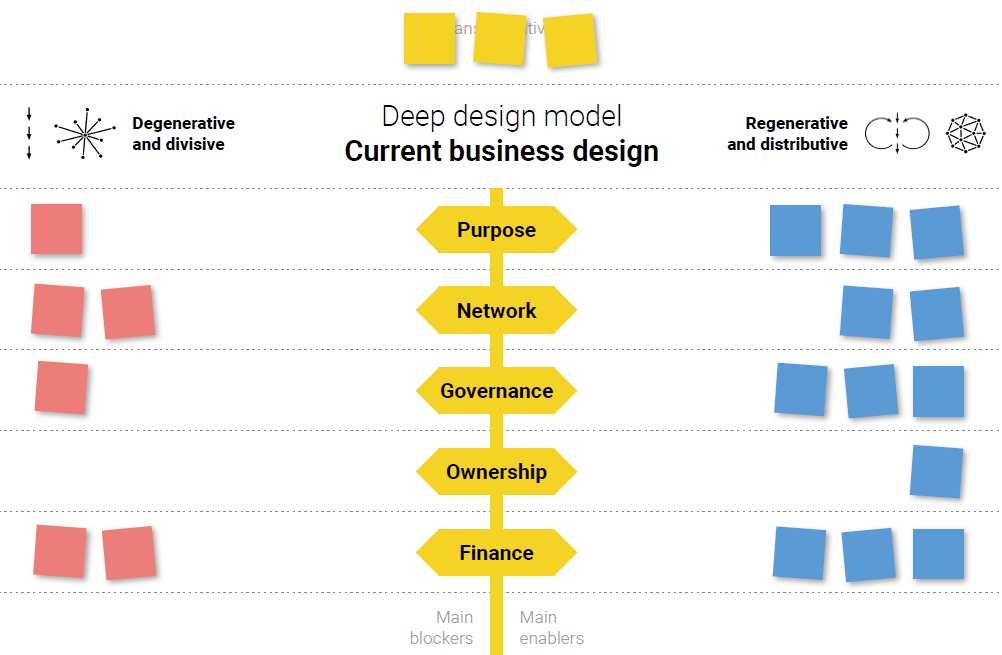

More action-oriented frameworks have also emerged, the flagship being probably the work that Doughnut Economics Lab has poured into their Doughnut Economics for Business Tool. The approach – rooted in the “Seven Ways to Think link a 21st Century Economist” that Kate Raworth explored in her book – suggests looking into a business or organization from the lens of the transition between a (relatively vaguely) defined Degenerative and divisive into Regenerative and distributive, along the lines of Purpose, Network (collaboration with stakeholders), Governance, Ownership, and Finance.

Most of the frameworks, mental models, and principles that emerged around regeneration point out that a transition from degenerative economics into regenerative economics needs to grapple with key questions around overcoming growth as a north star, and most of all the need to go beyond globalism and universality, towards more context-based solutions.

Despite these clear pointers, the work (and the narratives) we’ve seen so far unfolding toward ideas of regeneration in business has been quite controversial. As excellently captured by a recent essay by Raz Godelnik in his “The Myth of the Regenerative business model”, there exists a stark contrast between the principles and ideas behind regeneration and the possibility for them to be truly expressed inside a business-as-usual frame, characterized by the need for growth, ever-increasing efficiencies, and soothing marketing messages.

In talking about Nestlè regenerative business efforts Godelnik says:

“The company’s strategic focus on optimization and efficiency is a classic sustainability strategy that is about doing less bad. This does not mean that it won’t create some positive impact, just that it is not what is needed to help make the food system more resilient. The pursuit of efficiency is what brought us in the first place […] The bottom line is that Nestle’s approach to regenerative agriculture is not offering a shift from efficiency (doing the thing right) to effectiveness (doing the right thing).“

Godelnik quotes directly another piece from Daniel Wahl saying that “Regenerative Economics […] fundamentally means starting new ways of working rather than improving the old ways” stressing the point that an actual regime shift, a paradigm shift even, is needed to really move the needle in overcoming the destructive patterns of modern capital markets which have put humanity on a trajectory towards collapse.

Godelnik’s judgment could be perceived as incapable of capturing the depth and breadth of an amazing cultural movement that is unfolding behind the word regeneration and I get that. On the other hand, I believe, the piece highlights an essential element of the discussion. Even if we accept the confusion in terms – fairly common in movements that are just unfolding – it needs recognition that most of the regeneration experiments so far done in business, especially large corporates, are often far from prototyping the level of transformation really required. More specifically two key pillars of business-as-usual are reasonably under scrutiny in Godelink’s piece: growth and efficiency.

Growth has been largely challenged in recent years to the extent that a post-growth or de-growth movement has emerged to promote the idea that we should be looking at qualitative and not quantitive ideas of progress, and that, in any case, as predicted so well in the Limits to Growth report in the 70s, infinite growth in a finite biosphere is – unsurprisingly and quite obviously – a recipe for disaster.

Besides growth – for which we may even have qualitative interpretation at hand thinking in terms of well-being – efficiency seems to me an even more problematic concept: lacking a reframing of desire, achieving efficiency is only an affordance for more consumption to come.

We know this since 19th-century economist William Stanley Jevons discovered the phenomenon – later named Jevons Paradox [1] after him – in which improvements in the efficiency of using a certain resource (such as energy or water) often lead to an increase in the overall consumption of that resource, rather than a decrease.

As Godelnik explains in the piece:

“The pursuit of efficiency is what brought us in the first place to have an intensive (and inhumane) industrial livestock system that works to maximize profits […]. With the expected growing demand for dairy, poultry, and meat any savings in GHG emissions due to efficiencies are likely to disappear, not to mention the need to use more land to support the increase in livestock grazing and grow crops to feed more farm animals.”

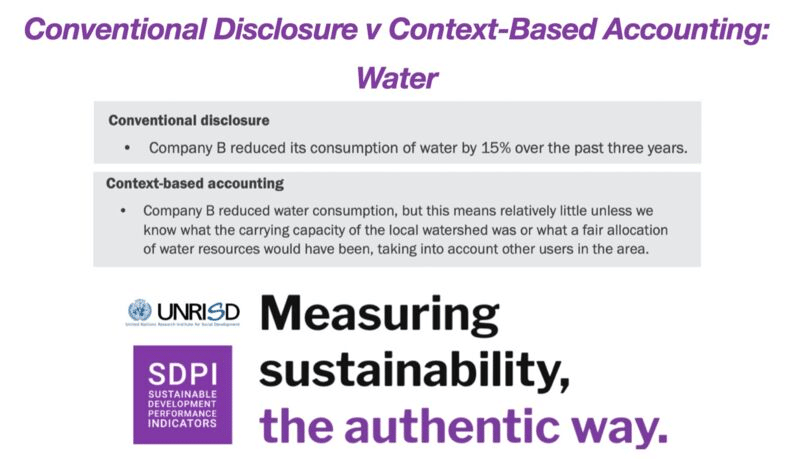

This clarifies quite a bit how de-contextualizing initiatives from their place-based network of dependencies can shape even an utterly negative development into a positive one: the more disconnection does exist between the contexts of production and those of consumption the less visible the embedded impacts will be to the end consumer and to society. The issue of decontextualization is so clear in the discussion around sustainability that r3.0 – a pioneering organization in regenerative thinking – has framed this need to reconnect to context as “Authentic Sustainability Reporting” claiming the need to do “context-based” accounting versus conventional disclosure.

The question that remains central is: if we dare not be blind to such crucial limits of industrial, globalized thinking that seeks easy solutions for wicked problems, and is able to only produce efficiency-seeking, growth-hungry, universalizing market strategies, what could be a credible rethinking of socio-technical systems that can be seen as a real starting point in building a regenerative alternative to the current shape of the economy?

The more we – at Boundaryless – develop our understanding of what it means to embrace regenerative thinking in product and org development, the more we seem to converge on the idea that such transition deals with contextualized, self-organization of stakeholders around production chains embedded in place, and webs of relationships.

Ultimately, we believe, reinventing the economic system and creating regenerative patterns is about helping stakeholders self-organizing around production chains, outside, or at the edge of the dynamics of global markets. We believe this needs to be done in a way that – ultimately, or at least partially – detaches production and consumption from the market, by connecting all the constituents in a relational space where they can “think as an ecosystem” and do not feel as isolated players in an unbundled and ultra-specialized market where the only strategies available are competition, and consumption.

In a recent book published in Italian called “Neomutualismo” (Neomutualism) authors, Venturi and Zandonai point out how new forms of self-organization for mutual interest are gaining new momentum – probably as an answer to the disintegration of the industrial model. Such initiatives are often community-embedded and place-based and focus often on producing two main types of outcomes: either the production of a set of shared services, that respond to every participant’s (mutual) needs, or the regeneration of the local environment, be it civic, or natural. These new, self-organized, embedded models of production often emerge, at least in our direct experience, in internal areas where community and place-basedness are inherently more tangible with respect to a cosmopolitan metropolis. In these (multiple) contexts, often small in scale, we recognize how the emergence of collective models of production is pinned on participants’ long-term commitments and skin-in-the-game, and works through direct, collective participation, distinguishing itself from the hyper-specialization of globalized markets and instead promoting a plural human development thesis: these initiatives need a real diversity of contributions to achieve some form of success.

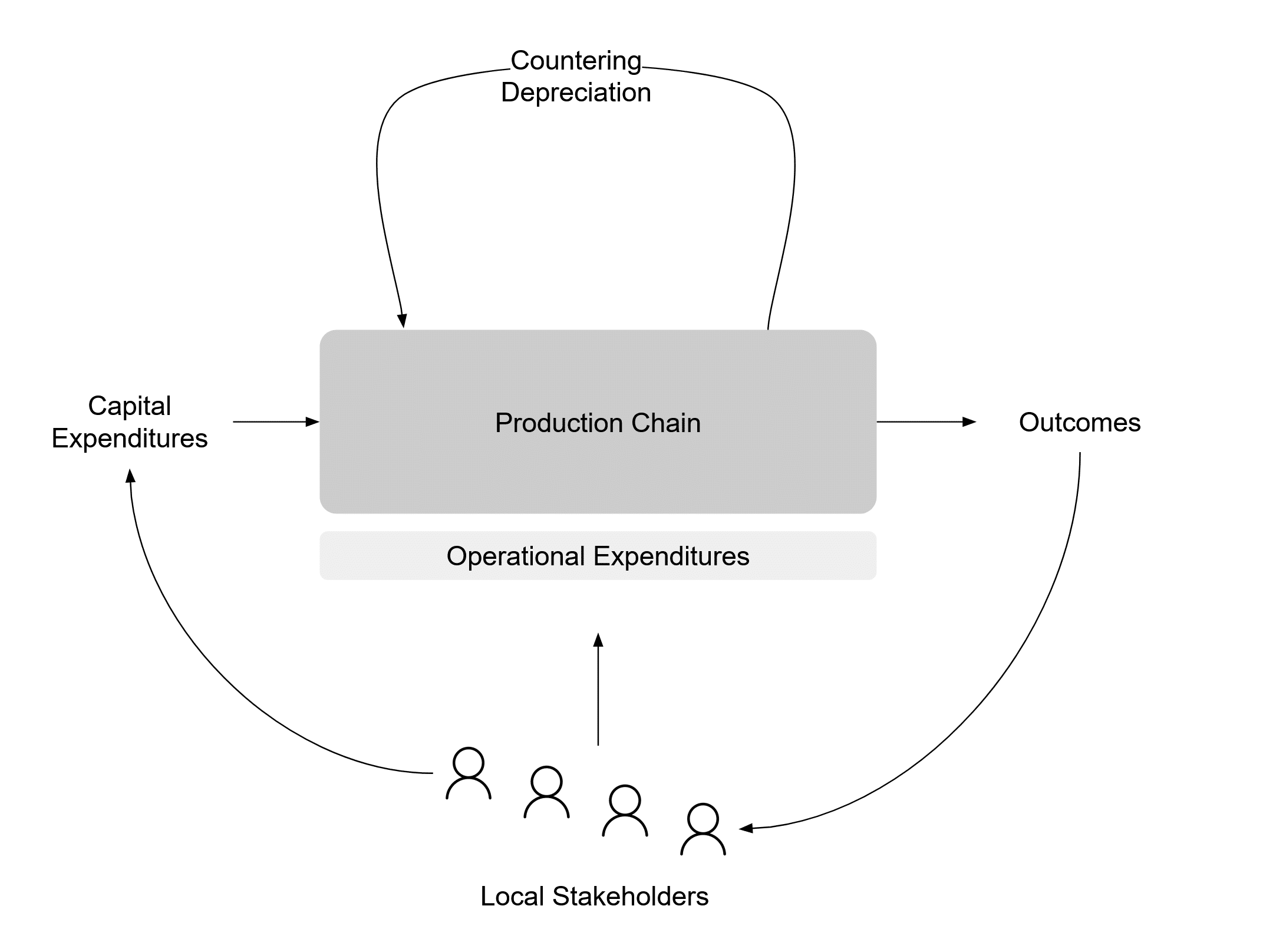

These self-contained production chains see consumers and producers self-organize to produce mainly two types of returns: direct and indirect. Being it services such as welfare (eg: an elderly care coop), education (a school), or the production of a particular product or commodity (for example energy production or agrifood, imagine running an olives orchard), these projects of organized co-production deliver often primary outcomes that can be socialized directly (through self-consumption) or sometimes traded on the market (at the interface between the self-contained system and the market economy) to generate profit margins.

Such processes can produce either:

- direct returns in services and outcomes (e.g.: imagine how a solar panels micro-plant can generate energy for the co-owners)

- discounts that would make the mutual players able to access essential services at lower cost

- monetary returns as a consequence of trading outcomes with the market.

Essential questions exist regarding the right caps to adopt when returning interest to invested capital. A pattern that we see emerging is that of capping investments – and thus returns – to what a participant in the mutual system can effectively consume. This is for example the approach that the Italian energy cooperative Energia Positiva has taken, by limiting the capital that cooperators can invest in the creation of a new solar plant to a 20x multiplier of their annual energy need. By building the plant and trading energy with the network, the cooperative then generates a marginality of around 10% of the setup cost of the solar plant every year after the installation – 5% of it is used to provide the cooperators with their energy needs (admitted that they invested 20x their needs in the first place this 5% covers their yearly needs) and the other 5% goes to repay the typical asset depreciation – as a solar plant normally have around 20 years life cycle (note that these numbers are not official and this is an intuitive framing).

In some cases, such processes can generate indirect, second-order outcomes such as the regeneration of cultural practices, reconstruction of core embedded skills such as traditional agricultural capabilities, the recreation of natural environments, the betterment of shared civic space and civics in general, and so on. These second-order outcomes are either normally perceived as valuable by the participants – think for example the regeneration of the spaces where participants live and engage, the positive effects on the landscape, or the enjoyment of the regeneration of relationship and culture – or even through the engagement of third parties interested in such second order outcomes. For example, I’m thinking of monetizing carbon sequestration from an organic natural farming CSA project.

In a few words: making it easy to organize capital and interest around key economic processes to be developed in a specific collaborative context can generate opportunities for sustainable and regenerative developments locally that really have transformative impacts. The key problem is that such solutions can’t be generalized, industrialized, and administered: on the contrary, they need to be contextually executed firsthand because a truly contextual response needs to leverage specific contextual capabilities to develop a solution that fits specific contextual needs. No centralized bureaucracy can do this.

The possibility of extracting common, recurring models of these processes is however certainly worth exploring. Characterizing how different production processes have diverse needs for capital investments, have specific asset depreciation dynamics, and how can they generate a certain marginality is going the be of massive importance to facilitate enterprising in the space. Indeed, besides the necessary contextualization, shared approaches do exist, and models covering CAPEX, OPEX, depreciation, margins, and returns… can be developed quite easily for most of the production chains in the economy of fundamentals. Shared toolkits will also likely be developed and we can possibly expect the emergence of meta-platforms that could, at the same time, provide enabling technological solutions and help interconnect experiences at broader regional and multi-regional scales.

It goes without saying that self-organized production chains naturally tend to be focused on foundational economies, first because those economies tend to offer the broader constituents base (everybody needs energy) and, secondly, because those economies can be developed in a place-based manner, with partial exceptions being, for example, energy transmission, manufacturing of technology-intensive objects, healthcare or information infrastructure for which a neo-mutualist collective would still be applicable but would need to span over broader spaces (national or even international) and be ancillary to broader pieces of policy or industrial development.

Clearly, enabling policies and subsidiarity between the local, embedded players, and national and supranational players will play a role in this development. Policymakers won’t certainly be kept out of the process and instead will have a substantial role to play, but the key point remains one: self-organization will be a major driver of the real paradigm shift in production because, by nature, industrialized, growth and efficiency-focused economies can just perpetuate the universalizing culture of consumption of business-as-usual.

In this exploration, we need to hold off our need to often (always) frame our ideas for new societal development as a u-turn. This transition towards a contextual and local reinvention of production chains is not going to be “clean-cut” and universal, not a transition FROM the existing mode of production TO a new one but rather a messy, synergistic process that humanity will express, most likely under pressure. Hoping that “this is the right thing to do and we’re going to fix everything” is exactly part of the approach, ethos and epistemic we need to overcome: such an emergent reorganization will certainly encounter local failures and – possibly and increasingly likely – larger regional ones and restructuring our socio-technical production systems can also be helpful to reduce the harm that such failures can produce and to learn in the process, as we can see in the quote below, extracted from an interview with applied complexity scientist Joe Norman on our Podcast:

“a very relevant principle of subsidiarity says whatever the function of an organization, whether it’s a governing body or part of an organization or function of the organization, the best scale at which to serve some function is the smallest scale at which it’s possible to do so […] This approach cuts the systemic downside without eliminating the evolutionary and exploratory upside is by bounding things essentially locally and allowing a lot of variety and exploration at those local smaller scales. […] when failure happens, which of course it does, you’re learning from that failure or you’re at least surviving it system-wide.”

Why changing the paradigm is hard

First of all, quite normally, exactly because it requires, also, a change of paradigm. Mindsets are not ready at all for a departure from centrally defined standards of development (such as SDGs), centrally developed policy, and market-stratified specialization.

We’ve developed most of our socio-technical systems with a theory of predefined roles and “obligations” in mind – this works great to calm down the expectations of our mechanistic minds – but we increasingly realize that the economy of the 21st century can be much more pragmatically interpreted with the filter of loosely-coupled interdependent systems of agents, such as – for example – Burgess’ promise theory.

Promise Theory is a framework for understanding and analyzing complex systems, particularly those that involve interactions between multiple agents or components. It was developed by Mark Burgess, a physicist and computer scientist, and is based on the idea that agents in a system communicate and coordinate their actions by making and keeping promises to each other. Promise Theory argues that systems can be understood as networks of promises made by individual agents and that the fulfillment or violation of these promises can have significant consequences for the overall functioning and stability of the system. It is often used as a way to model and analyze the behavior of distributed systems, such as computer networks, but has also been applied to fields such as economics, biology, and social science.

According to the Promise Theory:

- people agree on each other’s assurances and undertakings through a process of negotiation,

- incentives are handled based on the outputs and outcomes delivered but also on the risk taken and the behavior displayed,

- the underpinning principle is that of self-commitment.

In an illuminating interview from 2019 on Jim Rutt’s podcast Burgess – explaining the organizational implications of his Promise Theory said:

“The farther downstream you are, the closer you are to the recipient of a promise in a chain of delegated promises [ed: an organization], the more responsibility you have for the outcome. […] if you ultimately try to blame someone else, the only reason for blaming someone else’s is because you didn’t keep your own promise to find that resource somewhere else”

In this passage, I see a stark similitude with our very own work on the 3EO Framework: looking at the organizations as a system of independent nodes, essentially making promises-based contracts to each other to achieve certain dynamic outcomes. If we focus on the key message here, this is that: if we acknowledge the complex nature of the reality we are ultimately responsible for our own promises and nothing else can be taken for granted. In a few words, the message is: first of all, self-organize.

Initiatives like the ones we’re describing in this piece, however, present non-trivial complexity in execution, namely:

- systemic lock-ins that prevent alternatives to emerge

- inherent hurdles in getting collective processes off the ground where entrepreneurial incentives are unclear

- the intimacy, empathy, and capacity to perceive nested complexity and deal with paradox needed to participate in such complex processes

Systemic lock-ins that prevent alternatives to emerge

We can identify two major lock-ins that would prevent (preferably place-based) self-organization around a production process: first, the fact that existing incumbents have a stratified right to manage the production of a specific process or, secondly, a certain level of incumbency due to infrastructure or monopolies.

For example, referring to the first question, education is normally provided by state-funded industrial schools that – besides lacking the capacity to provide an education that is contextualized to the learner context – are paid by taxes to which one can’t subtract, thus making it hard for a family to invest into creating alternative, subsidized and co-organized educational projects. On the other hand in fields such as energy – or infrastructure in general – the role of centralized, high CAPEX backbone networks is an essential enabler for local nodes to emerge and grow: think of the role of the energy network in enabling the pooling of resources locally around community-owned solar plants that can trade excess energy, thus making it possible for new types of financial agreements to emerge such as the ones described above.

Furthermore, lock-ins exist at a personal level as contributors to the self-organized, bottom-up economic models we describe in this piece are often made precarious by the dynamics of the market. For example, a designer or entrepreneur willing to work in kickstarting similar processes may find herself locked into contributing to the industrial economy by the need to pay rent and make ends meet, leaving little time to devote the energy and thinking needed to building the alternative.

Inherent hurdles in getting collective processes off the ground where entrepreneurial incentives are unclear

As enablers consolidate for ecosystemic ventures to emerge we’re learning that building cooperative systems present challenges on its own. The theory of venture building that we’re used to, especially as it consolidated in the last few decades, is rooted in the idea of entrepreneurial motivation and capital investment. The assumptions are that:

- Entrepreneurship can drive things forward at the start and then reap most of the benefits through either the distribution of the business profits or the progressive dilution of ownership toward so-called exits

- Capital can create capabilities, meaning that the capabilities to run and grow a venture can be essentially acquired or developed mainly through the deployment of capital.

So what happens when some of the premises that made the entrepreneurial system of the XXth century so solid suddenly disappear?

We are, indeed, dealing with systems that are:

- systemic mission-oriented in nature

- inherently not supposed to maximize profits (but stakeholder returns)

- supposed to run a stakeholder-focused governance

- not targeted to end up in “exits”

Despite different scales, similar problems have emerged already in the context of web3 where the ethos of building collective systems and hyperstructures (“public goods which create a positive-sum ecosystem for any participants”) has been prevalent. The paradigms of “progressive decentralization” and “exit to the community” have pointed out certain experimentations where the original founders – responsible for the design and bootstrapping of the system – look into a potential repayment of the massive initial efforts (needed to get anything really off the ground) through the monetization of an initial amount of “governance tokens” (that can be seen as the equivalent of cooperative shares) as they eventually devolve the governance of the system to the community they built it for in the first place. Those interested in the web3-related discourse can look here and here for more of our thinking on the topic.

There are also other patterns that might help create incentives for the early entrepreneurs bootstrapping the systems:

- entrepreneurs are motivated to play one of the many key roles that – once bootstrapped – the system will need to run, such as that of a provider of one of the systems enabling services, management, communication, etc…

- entrepreneurs motivated by the possibility to become a productive entity in the ecosystem that is being bootstrapped – imagine a company that can install solar panels to help bootstrap a solar cooperative to later sell installation services to all the customers in it.

On top of this, the fact that these initiatives often rely on creating “enabling constraints” and patiently nurturing capabilities that can’t be created with capital, but only developed over the long term makes things even harder. An excellent example could be natural farming: as the skills needed to master such processes take a lot to learn and develop (quite often relying on inter-generational learning), and need to be deployed in the context with relevant context adaptation needed, capital is only a part of the picture and the patient building of a web of relationship with place and community is as much important.

The intimacy, empathy, and capacity to perceive nested complexity and deal with paradox needed to participate in such complex processes

The last point that makes the adoption of such a perspective of reinvention of the socio-technical system so hard to envision is due to the lack – better atrophy – of basic capabilities to engage in collective enterprising, due to the sterilizing nature of the post-modern industrial complex we’re all immersed in. In a recent interview with a friend, one that is involved in a wheat production cooperative that is pioneering most of the production paradigms described in this post, he mentioned the incapability that many have to deal with what he called the Polemos, the capability to engage with conflict. Conflict is – by the way – only one of the many aspects of human experience that we have lost touch with and that will be essential to build the new breed of contextual ventures that are needed to reinvent society. Empathy, vulnerability, and intimacy – all capabilities that are essential as well – have been also eliminated from the average life of the average consumer, and – whoever has ever engaged with collective enterprising knows – they are an essential part of venturing.

Furthermore, as we reinvent entrepreneurship in these embedded and cooperative forms we discover that the human development thesis needed to get such initiatives off the ground is ever more complex and entails a massive diversity of skills, and styles of contribution thus requiring the capacity, in the leadership, to see through the whole spectrum of contributors needed to get any of these initiatives off the ground.

Conclusions (for now)

In this piece, we started by briefly analyzing the current discussion around regeneration and confronted it with the outstanding contradictions in expressing regenerative approaches inside the frames of business-as-usual, more specifically the lures of universalization, growth, and efficiency-seeking. We argued that any credible response to the crisis of the industrial society – as it reckons with the complex, embedded nature of the world – can be only expressed as a synergy between contextually and locally expressed solutions, where all stakeholders self-organize around production chains, and evolving supra-regional policies, expressed by governments, and co-evolving market-driven forces.

We argued that the transition will be messy and involve failures, and that facilitating the emergence of local, contextual solutions through models, meta-platforms and policies can provide a way to trim down such systemic risks and partially edge communities towards shocks while, at the same time, contribute to the regeneration of local cultures, skills, and capabilities.

Policymakers should interpret these reflections as a nudge to design policies that act more as enabling constraints than directives. They should also aim at addressing systemic lock-ins that prevent context-based initiatives to emerge. Business leaders should look into how their organizations can develop synergies with local players, and develop more “subsidiary” business models that can enable and interconnect contextual solutions more than provide universal services and products.

If you’re a business leader or policymaker interested in integrating these insights into your organization’s strategy please reach out through the form below.

[1] I suggest this podcast to go deeper into the topic

Srpecial Thanks to Alessandro Pirani and Stina Heikkila for an early review of this piece.