A Viable Path to Regenerative Organization Development

From adopting a Regenerative lens to Enabling Constraints to fully Closed-Loop Value Creation: Rethinking Organizational Architecture for Multi-Capital Systems

Simone Cicero

Lucía Hernández

Alessandro Pirani

Introduction: Beyond the Profit-Loss Forcing Function

As the pioneering Cynefin framework, developed by Dave Snowden over many years, has taught us, it’s always a good idea to prepare organizations to face different types of environments. Organizations may face a complex, complicated, simple, or chaotic environment of external and internal factors. While accounting practices are generally predictable and straightforward, ensuring continuity of production is typically much more complicated. Producing the innovation needed to stay competitive in ruthlessly evolving markets, an activity based on ever-changing relationships, can be a more complex challenge, especially in specific sectors.

For the past decade, many organizational designers have become more complex-aware, and the idea of managing organizations as complex adaptive systems through “enabling constraints” instead of top-down bureaucratic structures has gained significant ground.

Enabling constraints – strategic limitations that can liberate innovation by providing clear pathways, boundaries, and rules – can help organizations emerge and adapt organically, finding coherence in relationship with market and customer signals, reducing brittleness and internal debt.

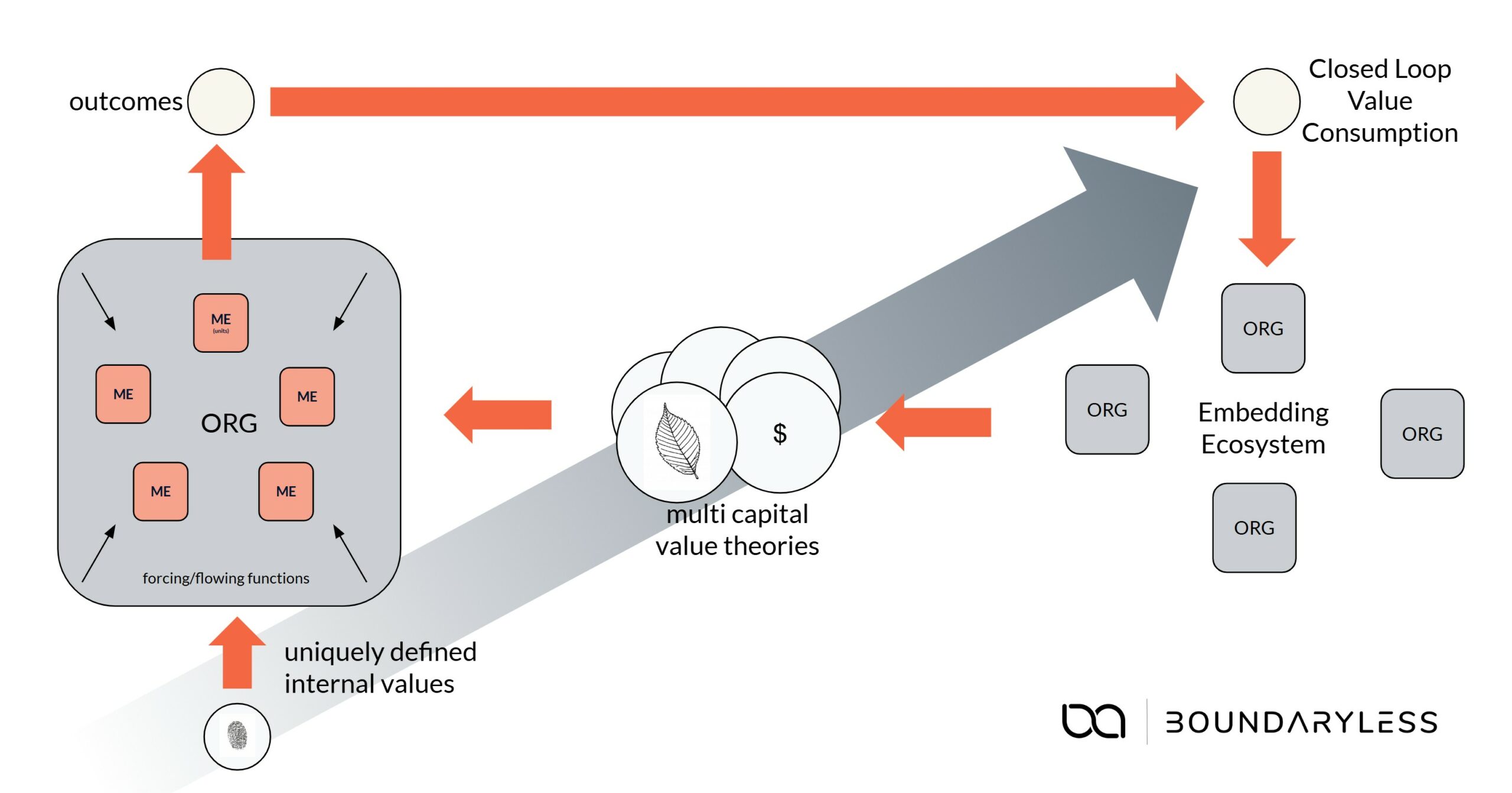

One of the most successful manifestations of a practical yet complex-aware approach has been to unbundle organizations into smaller, independent units, sometimes referred to as micro-enterprises. In this mode, championed by companies like Haier or Amazon, a model where autonomous units with their profit-and-loss statements evolve through a simple “forcing function” – that of being “profitable.” – or relatively simple variations or adaptation of it, that thy to avoid building up a lot of complicated rules and superstructures. Organizations can easily evolve towards new management systems by breaking down capabilities and allowing the market to transform them from within. This is what we call – at Boundaryless – organizational unbundling or the platform organization, and for which we’ve developed the 3EO Topology and framework.

This “market inside the company” approach has proven remarkably effective at aligning organizational behavior with external environment signals. It’s Ashby’s Law in a nutshell: improving the organization’s capability to manage a spectrum of environments, up to highly complex ones, by matching the internal complexity and adaptability to the external complexity of the ruthlessly evolving 21st-century markets.

Yet as we witness the emergence of key questions around the need for regenerative business practices, bioregionalization, B-Corp movements, and stakeholder capitalism, a fundamental question arises: what happens when the constraints we impose extend beyond traditional economic metrics? How do we re-embed production into place and landscape, on a local-regional basis, to increase accountability to the flows and stocks of resources it uses? How do we design organizational architectures that can handle multiple forms of value – financial, environmental, social, and cultural – without collapsing into a bureaucracy?

The traditional approach to constraints-based organization modeling, while powerful, reveals limitations when confronted with “regenerative constraints” – new intentional limitations that prioritize a different set of long-term positive outcomes over short-term financial optimization.

If only measured from a profit-oriented lens, these constraints are seen as increasing operational costs and complicating supply chains, with the value they create being hard to monetize in traditional markets. Yet they may become essential for survival in an era of political turmoil, ecological breakdown, conflict, and resource scarcity.

This article explores the evolution of contemporary, constraint-based organizational development approaches toward “closed-loop regenerative value creation” – a framework for organizations to define, capture, circulate, operationalize, and redistribute multiple forms of value through intentional ecosystem orchestration.

How Enabling Constraints Work

Before exploring new territories, it’s crucial to understand why the enabling constraints approach has been successful. In its classical implementation, the model works through a simple but powerful mechanism. Organizations create internal market dynamics by exposing micro-enterprises to real customer demand and competitive pressures. Each unit must generate positive profit-and-loss results: a forcing function that aligns internal behavior with external market realities.

In our experience, organizations often adopt a nuanced approach. Strategic constraints are introduced alongside market signals, such as the need for market coherence: “the customer must hear one voice” – typical of large groups – or “all services must integrate through a single platform,” which is fairly present at scaleups.

These constraints modify the market forcing function within the organization, resulting in monopolies or bottlenecks (e.g., a “sales platform”), and units adapt to the system, finding new ways to collaborate to create value while respecting these limitations. These limitations, by the way, generate adaptability and accountability trade-offs: scapegoating becomes more frequent, and the information flow between the customer and the organization narrows. In this situation, you need a stronger culture and a more editorial leadership to take more responsibility for coordination and close the gap.

Market pressure and the strategic constraints imposed ultimately drive continuous organizational evolution. Units merge, split, or reconfigure based on their ability to satisfy market demands and in line with internal policies. If the pieces are small enough and the constraints are not too rigid, evolution still leads, and innovation and performance emerge from a system that is flexible enough.

This model has proven particularly effective in tech companies and service organizations where value creation is information-based and market feedback loops are short. Companies implementing variations of this approach, from the radicality of Haier’s Rendanheyi, after which the 3EO is based, to Amazon’s two-pizza teams and programmable interfaces, have shown superior adaptability compared to traditional hierarchies.

However, as organizations grapple with regenerative mandates, the limitations of purely market-driven forcing functions become apparent.

The Emergence of Regenerative Constraints

Regenerative constraints represent a new category of organizational limitations beyond traditional profit maximization. They’re not new: pioneering companies have been applying them forever. But unlike conventional strategic constraints that modify profit pursuit, regenerative constraints often require organizations to optimize for outcomes that may not be immediately monetizable or may even reduce short-term profitability.

These additional constraints often arise when the organization starts to ask new questions, beyond monetization or profitability: how do we relate with the stakeholders that exist at the edge of the organization, and how are they impacted (customers, providers…)? Whose voices are included in decisions that the organization takes? To what extent are the workers involved? What happens at the interfaces with communities and ecosystems?

Consider a recent experience with a technology client: they chose not to charge for the software required to operate their hardware products. While this decision reduces short-term revenue, it reflects a regenerative logic: prioritizing user sovereignty, autonomy, and relational trust over extraction and exploitation. By ensuring access without dependency, the company enables users to fully own and adapt their tools, redistributing value and fostering healthier, more empowered ecosystems.

In many cases, embodied regenerative framings for product and organizational development can deliver positive-sum results. For example, organizations engaging in community co-creation processes can identify opportunities for waste reduction and recycling, or regenerate a place, such as using a semi-abandoned warehouse to set up new offices or production facilities.

On the other hand, we must acknowledge that organizations implementing other regenerative constraints may face systematic increases in operational costs. Sustainable suppliers charge premium prices; ethical manufacturing requires additional certifications and oversight, and circular economy principles may demand new operational approaches that require capital and operational expenditures. These constraints cannot be absorbed through efficiency gains or passed on to customers in competitive markets; rather, they require an understanding and recognition of the new forms of non-monetary value created in these processes.

The challenge is: how do we design organizational architectures that use regenerative constraints to create resilience and adaptability without compromising on viability? How do we make other forms of value visible and an element of our design framework aligned with life and value-affirming principles?

Defining and Operationalizing New Systems of Value and “Flowing” Functions

The answer lies in understanding that regenerative constraints operate through a systematic stack that transforms the flow of value in organizational systems.

Ecosystem Value System Redefinition

The foundation of regenerative organization design requires expanding the definition of value beyond profit maximization. This isn’t measurable using CSR or ESG metrics; it involves fundamentally redefining what the organization optimizes for within broad ecosystem interactions, which extend even beyond the business ecosystem surrounding the organization.

In traditional market-driven systems, the driving force is clear: maximize profit and minimize losses—this metric guides the decision-making of product units. However, regenerative systems differ and are built on a diversity of unique theories of value; organizations must establish multi-capital value frameworks for transparent decision-making.

This redefinition process involves identifying the forms of regenerative capital the organization wants to create, consume, and depend upon. A non-comprehensive list may include:

- Financial Capital: Traditional monetary flows and asset accumulation

- Ecological Capital: Ecosystem services, resource regeneration, increased biodiversity, carbon sequestration

- Social Capital: Community relationships, people development, stakeholder trust

- Learning Capital: Collective capacity for inquiry, knowledge creation, and adaptive innovation

- Cultural Capital: Transmission of shared values, meaning, and identity through stories, rituals, and collective memory

- Teleological/Spiritual Capital: Sense of purpose, meaningful action in service of life/Humanity, interdependence, and interconnectedness.

These forms of capital can substitute and enhance each other, but only when organizations develop frameworks for understanding, acknowledging, measuring, and exchanging them, optimizing multiple value types simultaneously.

Multi-Capital Forcing Functions

Once value systems are redefined, these new values must be translated into specific directions, enablers, and constraints to guide the single units, micro-enterprises’ behavior in the broader organizing system.

An architecture based on autonomous units with clear performance metrics, with units that operate in touch with their specific and embedded local and operational context – we believe it’s essential to achieve regenerative outcomes.

If approached otherwise, with a centralized responsibility where such objectives are left to be accounted for at the whole, monolithic organization level, they might never be delivered: the complex and systemic nature of such outcomes makes it intrinsically problematic to plan and control. Rather, they can emerge organically from all the complex interactions between the units and between them and the ecosystem of partners and customers.

Therefore, a new regenerative “forcing function,” or rather “flowing and resonance function” (to acknowledge a more organic nature) would need to include and provide the units with new metrics.

These new regenerative enabling constraints might start from basic Resource related Metrics – focused on environmental impact- such as biodiversity, soil health, water quality or waste reduction, Social Impact Indicators related metrics – related to communities impact in the context that embeds the organization – such as economic development, or social cohesion might also be included. Some organizations might consider contributing to the Commons, like open-source code development or open-access research publications, as regenerative and worth pursuing. The list might go on to piggyback on the list of regenerative values mentioned above, depending on the single organization: a common trait that regenerative constraints will likely share is, by the way, the ultimately long-term focus they embed.

Translating a multi-capital/multi-value framework into operational flowing functions will ultimately require accounting for tangible stocks and flows that micro-enterprises depend on, similar to financial accounting.

Capturing Regenerative Value

Once we project regenerative indicators in the organization’s books, starting from the small units that make up the organization, a key question arises: how do we utilize such value to drive the micro-enterprise’s capability to exist, evolve, and thrive in harmony with its surroundings in the ecosystem?

Given its complex and contextual nature, which makes it rarely “tradable,” regenerative value requires more sophisticated capture mechanisms.

Intangible Returns and Secondary Effects

The immediate source of regenerative value capture comes through secondary positive organizational impacts, for example:

- Talent Attraction and Retention: Organizations known for meaningful regenerative impact attract higher-quality talent, reduce recruitment costs, and experience lower turnover rates.

- Brand Premium and Customer Loyalty: Authentic regenerative positioning enables premium pricing, customer retention, and market share protection in competitive landscapes.

- Operational Resilience: Regenerative supply chain practices, community investments, and ecosystem health contributions create operational advantages during disruptions, resource scarcity, and regulatory changes.

Despite not being directly monetizable, organizations can see impacts revert directly in the bottom line (like improved sales potential or reduced hiring costs) or indirectly accept lower marginality in Micro-Enterprises in the face of lower cost or better support functions, like HR.

Monetization and Externalization Through Credits

As regenerative practices mature, environmental and social value can be converted into tradable credits or certificates that generate financial returns. We’re familiar with Carbon Credits and Sequestration Certificates – organizations that create measurable carbon sequestration, emissions reduction, or renewable energy generation sell these outcomes in carbon markets, and similar patterns are emerging in other sectors. Experiments in Biodiversity and Ecosystem Service Credits for habitat restoration, species protection, watershed management, and soil health improvements are ongoing, so the real applicability remains unclear. Europe is now leading the way with new Nature Credits, creating a framework to recognize, certify, and reward nature-positive actions — from regenerative agriculture to ecosystem restoration — while mobilizing both public and private capital to close the biodiversity funding gap. Social Impact Bonds and Community Development Credits can also be explored by organizations looking to generate regenerative impacts despite not representing monetization. Intellectual Property and Knowledge Commons like Open-source development, methodology creation, and collaborative research, are historically harder to monetize, but mechanisms are emerging for open-source developers to monetize contributions.

Closed-Loop Facilitation and Ecosystem Orchestration

The ultimate step towards a regenerative model is when organizations evolve from implementing internal regenerative enabling constraints to orchestrating closed-loop value creation and consumption across the ecosystem. This transition allows going:

- from the idea of a single player trying to extract value from regenerative practices with the aim of monetizing it;

- towards a model where value exchanges close-loop inside an ecosystem manner, favoring the creation of new theories of value specific to certain ecosystems of relationships.

Closed-loop systems create self-sustaining value circulation mechanisms where some participants’ outputs become others’ inputs, minimizing waste and maximizing resource utilization without the need for market-making and monetization, as value is immediately recognizable for ecosystem actors.

Given the inherently “embedded” nature of most of the regenerative theses of value, and their desired impact on supply chains, and therefore landscapes, and communities, building them as closed-loop systems requires coordination across diverse organizations. Often, a regenerative ecosystem involves multiple private companies, community organizations, government agencies, research institutions, and civil society groups – each with distinct value priorities and operational constraints. Effective systems need protocols for translating different forms into utilities and rights.

Such closed-loop systems would require shared infrastructure investments, such as renewable energy systems, waste processing facilities, or knowledge management platforms, that exceed the capacity or risk tolerance of any individual organization. Such elements require collective governance structures that reflect the nature of the cooperation needed to happen, to coordinate diverse stakeholder interests while maintaining decision-making efficiency and accountability for collective outcomes.

Such investments would require a shift in thinking about return expectations. Traditional business investments optimize for short-term financial returns with clear exit strategies. In contrast, regenerative investments require patient capital approaches that yield long-term returns through multiple value channels and intangible means.

Regenerative initiatives generally have a multi-scale nature: multi-scale interventions featuring a portfolio of actions happening at different scales, levels and inside and outside the organization. Shorter regenerative cycles occur within larger cycles, and value generation and multi-value returns on investment can occur in different phases. Some things are certainly faster to improve than others: for example, incorporating plants, or natural light, and natural materials into an office space can enhance employees’ well-being, reduce stress, and increase productivity in a reasonably short term and be under direct control of a single firm (or micro-enterprise).

But beyond this complex, multi-scale nature, such interventions typically require a long-term development cycle before the high-impact outcomes materialize to maturity. This demands investment approaches that can handle extended uncertainty while maintaining organizational commitment and stakeholder engagement. Investors in regenerative initiatives must ideally be part of the same value production system and be prepared for returns in multiple forms, not limited to equity appreciation, learning, brand reputation, or signaling, but also in the forms of claims to actual ongoing benefits that extend beyond traditional financial returns. These rights can take several forms, for example:

- Outcome Access Rights: Investors might receive guaranteed access to the regenerative outcomes they help create – renewable energy at reduced costs, carbon credits for compliance, community-based services (e.g., education, housing, workforce development), priority access to innovation platforms, shared intellectual property or knowledge that enhances their capabilities.

- Governance and Steering Rights: Proportional influence over ecosystem development priorities, technology deployment decisions, and standards definition will produce valuable governance rights as ecosystems mature.

The key insight is that regenerative investments create multiple value forms captured through diverse rights structures, enabling sustainable returns even with modest traditional financial metrics.

A practical implementation approach

As organizations evolve from traditional constraint-based approaches to closed-loop ecosystem orchestration, they must define their unique theory and perception of value.

Their internal value measurement systems must include regenerative outcomes alongside traditional financial metrics for market performance prosperity, beyond survival. Pilot projects can demonstrate the connection between regenerative activities and organizational performance, helping to measure both direct and indirect benefits, such as talent retention, brand enhancement, operational resilience, innovation acceleration, and identify the right accounting mechanism.

Valuation Adjustment Mechanisms (VAMs) regulating a micro-enterprise budget will have to include regenerative outcomes alongside traditional profit and loss targets, and micro-enterprise leaders will have to understand multi-capital approaches.

The organization must explore its regenerative ecosystem and look beyond simple “customer needs.” It must consider suppliers, communities, competitors, and other stakeholders facing similar environmental and social challenges.

Collaborative projects that create shared value for multiple ecosystem participants may become the ideal next step in building a “last-mover” advantage rooted in legitimacy and cooperation. Non-extractive token systems representing non-monetary value flows may also be useful, beyond carbon credits, to support value circulation inside the ecosystem and to distribute governance, access rights, or knowledge agreements enabling value exchange across all participants.

Conclusion: The Evolution Toward Regenerative Organizations and Ecosystems is underway and requires entrepreneurs

The transition from traditional enabling constraints to closed-loop ecosystem orchestration represents a radical operational upgrade, requiring a fundamental evolution in organizational purpose and identity. Organizations are discovering that their long-term viability depends not just on extracting value from ecosystems, but also on enhancing ecosystem health and resilience, and leading ecosystem stakeholders toward shared regenerative challenges.

This evolution preserves and enhances the proven principles of autonomous micro-enterprises, clear forcing functions, and market-driven adaptations that have enabled organizational success in complex environments.

These foundations are essential for two reasons: first, to balance the need for business viability with a genuinely regenerative vision, and second, to avoid falling into a trap where we expect regenerative outcomes to naturally proceed from a bureaucratic and centralized process, such as with CSR and ESG.

A regenerative approach would begin with autonomy and decentralization, extending to encompass multi-capital value creation and ecosystem-scale coordination, ultimately leading to partially closed-loop systems with increased opportunities to valorize various forms of value.

The frameworks and implementation approaches outlined in this article provide a foundation for this transition; however, the field remains open to innovation and experimentation. Organizations that invest early in developing regenerative capabilities and ecosystem orchestration expertise will likely discover advantages that compound over time, creating sustainable competitive positions based on collaborative value creation rather than extractive competition.

The question is no longer whether organizations need to incorporate regenerative constraints, but whether they can evolve these constraints into an operating model (RegenOps) and develop ambitions to orchestrate ecosystems around them, strengthening their strategic position.

Organizations that master this evolution will play crucial roles in creating the numerous regenerative economies for our planetary future, while building resilient and adaptive enterprises capable of thriving in an era of profound system restructuring.

Simone Cicero

Lucía Hernández