Contracts and the Future of the Firm

How ubiquitous contracting can speed up the crisis of the Industrial Age Bureaucracies.

Simone Cicero

Abstract

The incredible leverage that industrial, mechanistic, scientific management has provided to organizations, coupled with their headless-ness, and lack of liability has produced immense harm on the planet and human society. Once every trace of context was removed from organizing, the tragedy of the Commons became the norm.

In this article, we argue that a new form of organization, based on small team units, shared services and widespread adoption of contracting has the potential to overturn the bureaucratic drive towards control and scale and reduce the harm that top-down, universalizing ideas of value, can potentially produce.

More in detail we:

- recap on the key traits of such an emerging entrepreneurial, ecosystemic organizing pattern across different spaces, from corporate management, to venture building to DevOps;

- explain how this constitutes a polarity with traditional top-down bureaucratic governance;

- cover how the space enabled by the maturation of blockchain technologies supporting many-to-many contracting and governance can complement the patterns emerging from more traditional organizational settings;

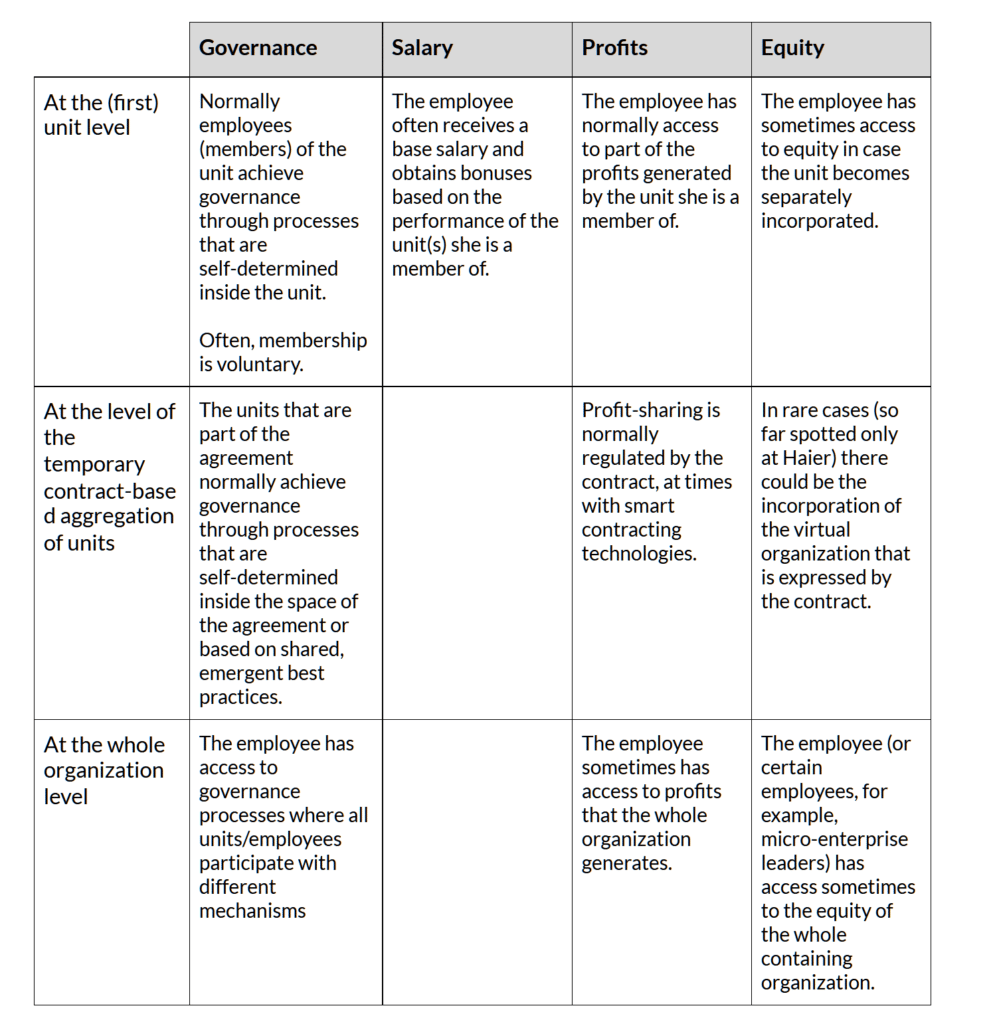

- quickly explain the different dimensions of skin in the game that are achievable through self-management, collective governance, profit sharing, and equity access;

- finally reflect on how such new organizational affordances — if coupled with a restructuring of what is salient to entrepreneurs in the face of ecological, social and industrial supply chain breakdown — can possibly favor the consolidation of a post-bureaucratic, post-industrial enterprising landscape that is more contextual to communities and landscapes, more pluralistic and thus conducive to a more convivial economy of care.

Special thanks to Emanuele Quintarelli, Stina Heikkila and Jacopo Romei for early reviews of the article.

A strong signal is emerging from the space of organization design and development: functionally integrated hierarchies are progressively being challenged by a shared practice of organizing work that is much more emergent, and complex-aware.

This shared emergent practice provides organizational structures featuring small interdependent team units, enabled by shared structures that provide support services. On top of this, unit teams usually coordinate with each other based on different mechanisms: such mechanisms aim at ensuring coherence without coercion.

Traits of such a way to organize can be seen not only in Haier’s Rendanheyi — the model that hugely inspires Boundaryless’ 3EO framework (where 3EO stands for Entrepreneurial, Ecosystem-Enabling Organization) — but in many other pioneering organizational models. We’ve been recently describing the overlap between different approaches to such a way to run organizations and we covered Haier’s Rendanheyi and Zappos’ Market-Based Dynamics, Buurtzorg’s independent teams, and even Amazon’s two-pizza teams (or, more recently STL teams).

Traits of such a way to organize have been also pioneered in software-centric organizations for a decade or so: the so-called “Spotify model” was among the first attempts to codify the breaking up of agile organizations into self-contained and autonomous small multi-disciplinary teams (squads) at scale. Such organizational behaviors are increasingly being codified and enriched in the DevOps community of practice. The DevOps sensation book “Team Topologies” — one of whose authors, Matthew Skelton, we had on our podcast recently — effectively identifies (from practice) four recurring team types namely:

- Stream-Aligned teams that have a cross-functional skills mix and the ability to deliver significant increments without waiting on another team;

- Platform teams providing stream-aligned teams an underlying platform supporting delivery (reducing cognitive load);

- Enabling teams that assists other teams in learning and managing change and innovations;

- and optional Complicated-Subsystem Teams normally managing legacy subsystems that are too complicated to be dealt with by a normal stream-aligned team or platform team.

Other experiences that should be considered part of the same evolutionary thread, can easily be identified in the meteoric success of Holacracy, and the long-termish one of Sociocracy from which Holacracy draws a lot of inspiration. With the key idea of “circles”, the sociocracy tradition brings up the need to give smaller, self-contained and self-driven units the ability to manage their value creation flows autonomously, without having to wait for “permissions”.

In the previous blog, we also explained how achieving the essential equilibrium between coherence and emergence is ensured in different ways. Haier achieves it by managing capital investment policies across emergent teams through industry platforms that dynamically invest in new “micro-enterprises”. Amazon distills KPIs through the cascading layers of the organization with a process called OP1-OP2 that helps the organization achieve its yearly overall objectives.

Companies are generally faced with the urgency of such a transition towards “unbundled” teams because they feel the pressure to become internally more “similar” to how the market behaves externally. After all, Ross Ashby and other cybernetics pioneers helped us to learn that if a system is to be able to deal successfully with the diversity of challenges that its environment produces, then it needs to have a repertoire of responses as nuanced as the challenges encountered in the environment.In a few words, monolithic organizations, bundled vertically in large structures, fail to cope with the dynamics of today’s markets: rapid change, user-drivenness, evolution, and exponentiality.

In the process of adopting such models — unbundling the organization — we believe that keeping the organization aligned with the market and society is essential: who’s in charge of making the case for a certain “team” or unit to exist otherwise? If the existence of a certain team is defined top-down and ex-ante, small teams can certainly become more efficient at doing the wrong things.

Transitioning into this new form of organizing: market and customer accountability

As organizations move through unbundling we believe that using approaches that give teams the responsibility to generate their own cash flow, manage their profit and loss statement, and let them attract new and multiple “customers” are to be preferred to models that apply more common unbundling recipe where budgets are allocated top-down.

This concern is particularly crucial in existing incumbent and large-scale organizations: in these contexts, companies have to address existing organizational debt and promote the exploration of more diverse business opportunities, a broader set of value propositions. In a startup or SMB settings, identifying org-wide directions (in relation to a smaller number of products) could be easier and thus easier to identify output metrics and translate them into input metrics for a few different nodes that compose the organization. In our experience, in the context of incumbents, shared services are also easier to identify as many teams already rely on common functional systems such as HR or IT. In the SMB/Startup settings identifying the shared services may be harder as the organization is still figuring out its market and thus the common processes to its evolving bouquet of value propositions in search of validation.

In our experience at Boundaryless with incumbent customers, adopting a pilot-to-scale approach based on casting such product-market-driven microstructures (micro-enterprises) on top of existing — often functionally integrated, sometimes divisional — “business units” and “functions”, is essential. You’ll possibly end up with two partially and temporarily co-existing structures: allowing existing units to “lease” workforce to these new micro-enterpreneurial units, and introducing SLAs with existing shared services providers (otherwise likely representing bureaucratic bottlenecks). This approach makes the transition easier to kickstart and injects the right level of “market-drivenness” into the process of unbundling the organization. In this way the existing structures are reshaped in a way that is conducive to business and influenced by market signal, a feature that may fall short if the organization implements blindly existing recipes of “spotifization” of more general scaled agile frameworks (SAFe) where the responsibility of market validation can easily be lost in the interaction of many parties and skin in the game is usually low.

Despite every approach can possibly driven to produce waste — in this sense, Haier’s Rendanheyi is definitely at the edge and testifies how the process of unbundling an incumbent shall lead to distributed P&L: Haier’s small units are fully independent, they self-manage their P&L, and coordinate only through dynamic contracts called Ecosystem Micro-Community contracts. Such a way of organizing effectively uses a “forcing function” to shape the organization continuously according to market signals more than to top-down decisions. At Amazon, instead, KPIs are implemented in a cascading systems that was ideated very early on in its history and is working to ensure the organization keeps focus without incurring in sclerotization and bureaucratization.

Elements of financial “accountability” and entrepreneurial “risk holding” of teams and leaders (a filter we’re borrowing from our friends at Dark Matter Labs) are essential to achieving an organizational transformation that doesn’t just “unbundle” for the sake of doing it, keeping all the other existing power structures in place. As Rachel Murch recently explained in our interview, you can unbundle an organization into circles, but then if one of those circles only has one internal customer, it is still effectively hierarchically depending on it.

The role of Agreements and Contracts: incubation and cooperation

The spectrum between hierarchical industrial organizations and complex-friendly ones can generally be described through a polarity between fully functionally bundled and fully unbundled: a military battalion on one hand and a “swarm” of interacting units on the other. While several companies adopt a unit-based model of organizing, Haier has advanced by adopting not only distributed and pervasive P&L (already quite a radical “forcing function” to adopt, as said above) but also a with a low friction smart-contract based system aimed at allowing teams:

- dynamically agree on shared missions and shared risks;

- automatically execute contracts based on transparent data.

So-called EMC contracts represent one of the most solid organizational innovations of the last decade and are enabled by the strong technological adoption that Haier has achieved internally. EMC contracts (quickly described in this post) are frequently set around shared objectives and often include players that are technically “external” to the organization. These contracts are based on (1) an ex-ante specification of the systemic objectives, (2) the explicitation of every unit’s contribution in that context, (3) a clear agreement on how the profits that the new so-called “user scenario” — a new product launch for example — will be redistributed to the units and (4) the potential investments that Haier, and co-investors, have to make to make it possible (such investments are not always required). To account for changes, EMCs can be iterated or disbanded, but only if all involved nodes agree.

Adopting such an automated contractual interface helps the organization to be more permeable: lacking an organizational boundary the contract plays its role, extending the concept of the organization way beyond its traditional “boundaries”. As we’ve been able to explain already, Haier also adopts another form of contracting aimed at making the creation of new units frictionless: so-called VAMs (Value Adjusted Mechanism) contracts. Such contracts are signed between the employee and an industry incubation platform, a structure that is missionized at deploying capital in certain fields. The company agrees with employees about CAPEX and OPEX of the new initiative on one hand, and about the upsides that the employee-entrepreneur could receive — bonuses, a percentage of the generated profits, and access to equity in the case of liquidity events — on the other. Not rarely, employees commit their own funds in the process.

Similar forms of agreements are commonplace in venture builders, and — even if often more informal — in other successful and transformative companies such as, for example, Amazon (with its STL teams) or Ping An:

“ [when the company creates a new business] we will bring in third-party shareholders, that provide immediate external accountability and reference benchmark for the value of the enterprise as it progresses … [management] will be set up as entrepreneurs, they will usually be required to buy stock in the company at a very early stage and commit their own funds. And they’ll typically be given a lot of stock as part of their compensation, the cash compensation will probably be lower. And if they do well, they can make a lot of money”

From Jonathan Larsen, Chief Innovation Officer at Ping An on Azeem Azhar’s Exponential View Podcast

If we look through this spectrum we can depict the transition as:

- from an industrial age idea of an organization where purpose is top-down set, direction is centrally defined (and control is exerted on it), work is administered (employees are attached to long term jobs), and leverage (the possibility to execute certain ideas at scale) is achieved through military-style management and push distribution;

- to a complex organization model where purpose is embedded into temporary agreements and contracts (dynamically changing), direction is entropic with little capability to centrally control if not through investment policies (that in any case depend on initiatives to start from the periphery of the organization with the entrepreneur in touch with the user). In these organizations work coalesces around objectives that emerge as are enabled by the constraints (such as the organization’s policies, artifacts) and leverage is achieved through the cultivation of communities of practice, ecosystems of adoption, network effects, and pull-based attraction.

Organizations all over the world populate this spectrum. To just name a few examples, most of those recognized as champions in “agile at scale” — such as ING group — are just moving away from hierarchical tradition; Amazon, by sporting the OP1-OP2 process that helps trickle-down outcome-based KPIs to each unit but only having self-managed P&L at divisional level is a bit on the middle; Zappos with its Market-Based Dynamics and self-managed P&L is experimenting with pushing to the right, together with Burtzoorg that effectively has self-managed P&L but a monolithic business model. Haier, as a pioneer, is almost fully on the right, with its Micro-enterprises and EMC contracts.

The contribution of DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) to explore new primitives of smart contracting

In the background of the transformations happening in the corporate world, a new wave of DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) is experimenting with other organizational primitives: could these tools complement the most pioneering corporates’ organizational models?

After all, Haier itself already runs EMCs as self-executing, smart contracts to ensure those agreements between entities — “nodes” in Haier’s jargon such as teams, or individuals — can be trusted: reputation is transparent and based on past performance. The execution of the agreements won’t be turned around only by means of the hierarchy’s power-over.

With regards to organizational innovations, DAOs are mainly experimenting with two radically new ideas:

- running trustful digital coordination infrastructures in trustless contexts;

- achieving decentralized governance decisions through the so-called Token-Based (and possibly on-chain) governance schemes.

The former is achieved through mechanisms where particular entities in the network can run so-called “validation nodes”: these nodes are in charge of maintaining trusted copies of a shared information ledger. Mechanisms used to ensure the integrity and consensus over the shared information ledger were traditionally based on proof of work (POW in short: the need to consume a lot of computing power, thus energy, to be able to write on the shared ledger) while emerging ones often leverage so-called proof of stake (POS).

In POS schemes validators have to financially stake (immobilize) capital — in the form of crypto tokens — over the long term, receiving financial uptakes in exchange for trusting that the network has the capability for future development that will valorize those tokens. Essentially, this paradigm allows the design and implementation of consensus mechanisms for shared data and information layers between parties, without the need for an institutional intermediary: a feature that may be essential in creating smart contracting mechanisms that work across organizations.

For what regards the latter, so-called token-based governance has been so far focused on using tokens to vote (with various different voting systems) on collective decisions. These voting mechanisms normally rely on weighing one’s vote through the number of owned tokens or adopt slightly different mechanisms where either voting power is reinforced with economic staking (as with quadratic voting) or time (conviction voting).

Some of these decisions are “on-chain” ones: some have a direct impact on the DAOs smart contract code — decisions about protocol changes are assimilable to a change of the organization’s policies — others impact treasury management and the effective allocation of funds: as an example, the purchase of a given asset whose ownership would be fractioned across members, like with Flamingo DAO. In other cases, DAOs decide on investing money into a given project, or team, that makes a proposal. Token-based governance is also used for “off-chain” decisions such as the election of roles, the definition of operational norms and sub-structures, changes to the DAO tooling stack.

Despite cryptoeconomics governance presents evident limitations that are now being the subject of a rich debate, we believe that, as more modularization happens, from the interplay of this space with the institutional innovations highlighted above a new organizational development space can emerge. Shared protocols & domain models, distributed data, inter-organizational interfaces: this emerging coordination infrastructure will likely be leveraging blockchains.

The Question of Skin in the Game

These emerging organizational settings allow a much more pervasive adoption of principles of “skin in the game” or the idea that by being involved in achieving a certain organizational goal you may face risks. By using a frame that was introduced recently by Dark Matter Labs, we may translate this idea of skin in the game as achieving, for all parties involved, a “balance of power, autonomy, responsibility, risk-holding and accountability in one actor” where:

- Power ‒ is the ability to shape conditions;

- Autonomy ‒ is the freedom to do things in a way that you deem fit;

- Responsibility ‒ is the burden/ability to take action;

- Accountability ‒ is the burden to justify your approach;

- Risk-holding — is bearing consequences of the results.

Normally, in a traditional industrial organization, the employee receives a salary and is attached to a certain job: salary is normally slightly adapted every year with bonuses that often relate to the performance of the whole organization. Salary negotiations are instead normally entertained between the employee and her direct supervisor, or HR. Different incentive mechanisms are often reserved for managers (essentially dealing with administering work and taking decisions).

In an organizational setting that works according to the dynamics of a 3EO (small units, dynamic contracting, and enabling support services) we normally have:

- employees that coalesce into teams (units);

- units that collaborate dynamically through agreements (contracts).

In some cases units can be created at “multiple layers” (as in micro-enterprises belonging to a certain “field” or as with circles being part of bigger parent circles) and things can be more complex to describe. On the other hand, the levers of skin in the game one can play with could be described — for example — as a particular configuration of what follows*:

*Assumptions: in this configuration employees are hired by the organization, units are emergent, contracts are dynamically created and destroyed. This is an exemplary configuration.

In such settings normally the whole organization level could be assimilated more to a government than a traditional industrial organization: taxing mechanisms are often used to gather part of the profits generated by the units and partially funnel them back to the whole. For example, during a recent interview with Boundaryless, former Executive Advisor for Strategic initiatives at Zappos Rachel Murch explained how Zappos expects circles to give back to the company 50% of their additional revenues; at Haier, this percentage varies and can account up to 70% depending on the level of support does the micro-enterprise (or EMC) receive for in the incubation phase.

“…when you think about a city, not everything that happens there’s a direct customer payment for. And so, for instance, one of the functions of a government is funding — taking tax revenue — and funding certain things for the good of the city. So, these can be anything from infrastructure, like roads and courts and the legal system to [anything] that is for the public benefit. And we’ve brought that same construct within Zappos, where we have a group that is called funded shared services […] that regardless of who you are within the organization, you can utilize. But those services still have their own profit and loss. It’s just the way that they get funded to do whatever it is that they do is through kind of the “government.”

From “Building Complex Organizations through Simple Constraints: Zappos — with John Bunch

By collecting such taxes, the organization effectively becomes a commons missionized to two major tasks: providing enablement and favoring cohesiveness and coherent innovation. The former task (enablement) is normally achieved by providing non-differentiating services to the units — services such as IT, HR, legal, finance.

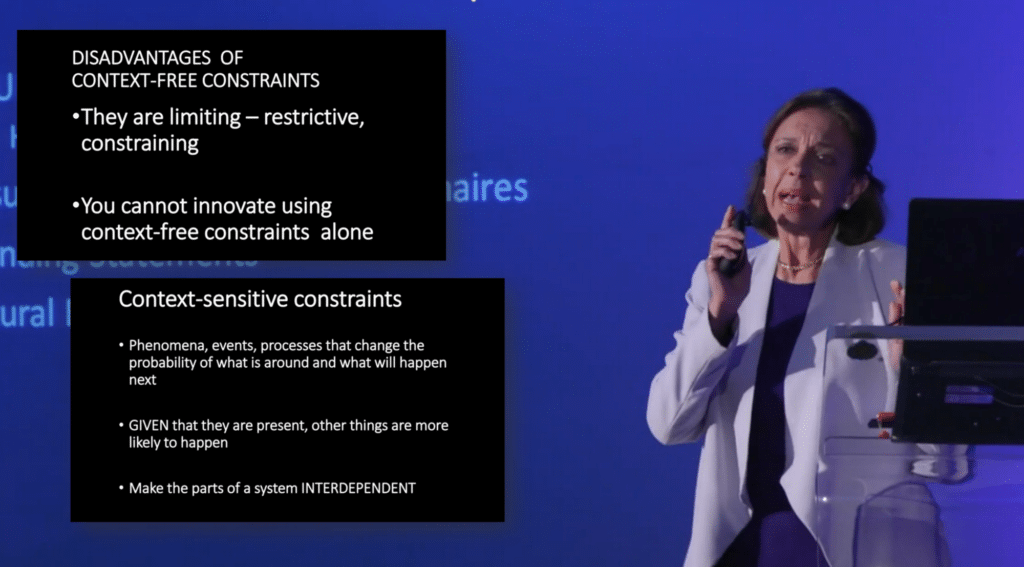

The latter instead (innovation) is to be seen as an emergent outcome of two major elements: context-free and context-dependent constraints. As renowned complexity philosopher Alicia Juarrero explains in this video: to enable innovation, organizations have to provide a set of context-free constraints on top of which context-sensitive constraints should emerge favoring interconnection, feedback, and loop-closing for growth. According to Juarrero, contexts-free constraints — such as purpose, or predetermined organizational policies and unit types — can effectively be seen as context-free constraints that bias the system in a certain direction (or a forcing functions) but only through the context-sensitive constraints that make things “interconnected” and “interdependent” (such as contracts that ensure that given this then that will happen, feedback mechanisms) organizations can create novelty.

In all respects, when dealing with 3EOs, the architecting of the general organizational artifacts and the rules (for example Zappos triangle of accountability, Haier’s positive P&L requirement, Amazon first order org-wide KPIs) can effectively be seen as context-free constraints that bias the system, while the emergent creation of new units, and the agreements between them (such as with EMC contracts), together with other feedback mechanisms, such as employee reputation, are essentially those context-sensitive constraints that favor the emergence of innovation. But does this recontextualization of the firm end here?

Conclusions: Pervasive contracting can change the nature of the firm and put an end to Bureaucracy

For contracting to achieve its full potential and aspire to a central role in organizing we need a new contracting experience. The technical tools and the organizational artifacts we have to build must cover the full contract lifecycle (desire, engagement, cooperation, exiting, extension), must allow faster and easier iterations, provide tolerance for error and changes, and avoid relying on middlemen so to avoid misunderstandings, fragilities. This is the main reason why we are developing the EMCos project: read more here and watch an introductory video from the OpenTalk conference here.

These new contracting experiences shall improve the adaptability of our organizations, while at the same time favor accountability and self-determined leadership. Contracts templates that help at the fundamental stages of the creation of micro-enterprises and enhance the possibilities for collaboration between them, will be essential in promoting a shared approach to organizing: can these common protocols possibly favor the “emergence” of a post-industrial organizational wave? How can this be transformative for our organizations, market, and society?

As these new tools bring new affordances they will reduce frictions to engage in collective entrepreneurship and self-determination and this will challenge the allure and dominance top-down bureaucracies, favoring organizational settings that allow a plurality of expressions. The ease of creating multi-unit disintermediated contracting will also challenge and transcend the idea of a bounded organization as we understand it today: suddenly as cooperation is expandable beyond the traditional boundaries and the fulcrum of organizational development moves away from the industrial centre, where should we expect this to move?

As Indy Johar said once on The Deep Dive Podcast:

“Now increasingly, we are able to do contracting on a many-to-many level, this means we are moving from a private economy to a civic economy and that changes the nature of how we construct value.”

Could we expect that as entrepreneurs are empowered to design and run small systems they will put their focus back into their communities, their landscapes? After all such contexts have been largely forgotten, and became the place where most of the externalities of the industrial age accumulated. The overcoming of industrial bureaucracy is partially a problem of technological affordances (we don’t have organizational technologies that are conducive to it), and partially an epistemological one: this advisable transition towards an economy that cares for the context will require a powerful reframing of what is salient to entrepreneurs (and participants).

We certainly don’t lack a systemic nudge: besides the continuous ecological and social catastrophes we are witnessing in real-time, industrial supply chains — optimized for scale, centralization and the discount of externalities — are breaking up in front of our eyes.

As umair haque pointed out recently “prices [of resources] are going to rise, probably exponentially, over the course of the next few decades [because] everything, more or less, has been artificially cheap”. Will the breakdown of these centralized and fragile systems drive a societal shift from globalism to localism (or better … contextualism)? Will entrepreneurs take on the opportunity to catalyze communities into reinventing anti-fragile systems for the production of societal needs?

For long, intellectuals such as Ivan Illich, Leopold Kohr and others have warned that the dominance of scale was harmful to the human experience and that industrialization (and globalization) has happened mostly at the expense of humans capability to enjoy the convivial practice of playfulness and personal relatedness. In a brilliant recent conversation with Lisa Gill, educator, poet and activist Bayo Akomolafe said that modernity has been a way to “enact constraints to our lostness”: so as the faith in modernity fades, rethinking what organizing means beyond the frames of the industrial age of scale, becomes existential more than essential.

As we step into this lostness we rediscovered, thanks to Covid-19, climate change and ecological breakdowns, to embrace a new attitude becomes key: the entrepreneurial thesis of the 21st century will have to come to life in a plurality of contexts.

“If we want to respond to the prospect of global self-extinction, we need to return to a carefully elaborated discourse on locality and the places of the human in the cosmos.”

From Yuk Hui “What Begins After the End of the Enlightenment?”