dRural Field notes: a Year in Review

In this post, we recount Boundaryless’ first year in the dRural project.

Boundaryless Team

In this post, we recount Boundaryless’ first year in the dRural project – a European Union-funded Research and Innovation project – which aims to connect the ecosystem of potential end-users and service providers in rural areas, delivering a broad spectrum of services while boosting economic growth and improving citizens’ quality of life. dRural is run by a consortium of 31 partners from 11 European countries. This blog post has been authored by Stina Heikkilä and Andrea Valeri and reviewed by Luca Ruggeri.

In the fall we published an article concerning the emerging trends and platforms to be set in the context of the dRural context. The article was produced as part of Boundaryless’ research role in the project, supporting the identification and design of use cases and requirements for the dRural multi-service platform. In this piece, we look back and recap what we have learnt during the first year of the project, including challenges faced along the way.

Setting the scene

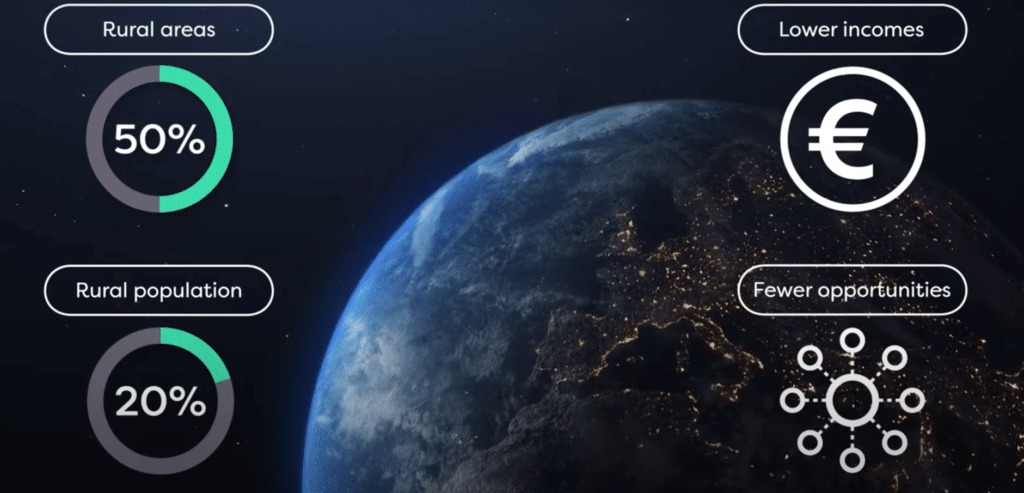

The dRural project is expected to improve the quality of life in rural areas and has the ambition to become the principal service marketplace for all European rural areas. The potential of digital transformation is expected to be unleashed in the rural pilot areas of the project, including by increasing cross-cutting applications and services, designing new industry and business processes and innovative business models in the pilots, and by overcoming the digital divide between rural and urban areas and developing the potential offered by connectivity and digitalisation of rural areas.

To achieve the objectives and impacts just described, the dRural Consortium is moving towards two main parts of the architecture of the dRural platform:

- The Core Meta-Platform, which enables interoperability, analytical processing, and data storing on the solution;

- The Marketplace, where services are exposed to the end-users through the dRural user interface.

This architecture was set before the project started and described in the project proposal and involves some fairly strict and significant assumptions and constraints. The core platform therefore starts from an existing technology, developed by the only software development partner in the project. Fitting ecosystem exploration and platform strategy design into such a pre-defined “solution” is one of the key challenges we have faced in the start-up phase of the project, since our approach is always ecosystem-driven and not as top-down as the project requirements necessitate (see more on this under key learning 3 below).

Within the above set-up, the dRural solution targets two types of services. Some of them have already been highlighted, especially those that are offered through the dRural interface using a templating-approach, allowing users to sign up and interact with peers on a marketplace (simple services), while we are still working together to identify those that require external data platforms and/or manipulations (complex services), such as aggregating healthcare and e-government data.

As explained above, a technical partner is building the first marketplace features based on previous work and research. In addition, as we explain more in detail below, we have worked with project partners to ensure that the services that are being developed in the dRural platform reflect the potential expressed in the four regional ecosystems involved in the project.

The dRural project is first being implemented in the four demonstrator regions Croatia, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden, each with a set of “native service provider” (NSP) partners (public and private sector entities) and one “local promoter” per region. The local promoters will lead the commercial exploitation of the dRural platform and its local instantiation during the project and beyond. The demonstrator regions are highlighted in the short teaser video above.

In this project, Boundaryless was invited to contribute to the platform design because we are uniquely positioned to provide the tools needed to develop platform experiences that take into consideration the need to enable scalable interactions that meet the goals and aspirations of the entities, allowing them to improve their performance over time while exchanging value in the ecosystem.

As most of our readers know, the Platform Design Toolkit (PDT) helps to co-create the design of a platform strategy behind any digital solution. It is an open-source methodology developed by Boundaryless to build multi-sided, transformative platform strategies to empower ecosystems in creating shared value.

While PDT has been downloaded and used by over 80,000 users worldwide, including large corporations, banking groups and international organisations, as well as grassroots organisations and public authorities, adopting this technique is about realizing transformational shifts in our economies and societies. In other words, it often starts with a mindshift. Luckily, we often work with organizations that are already some way down this path, however, we know that adopting a new mindset and language still takes determined efforts.

So, how do we adapt to a situation where we want to instill platform thinking in a 31 partner consortium, and where partners bring widely different aims and methods to the project?

Throughout the year we harmonised as much as possible other complementary approaches to service ecosystem building and business modelling that will be used.

In the three key learnings below, we highlight some of the challenges we’ve faced in the first year of dRural and how we are planning to move forward in the next phase of the project.

1. Achieving Platform-Ecosystem thinking literacy

The first challenge we faced was to be expected: introducing platform-ecosystem thinking was not going to be a walk in the park. As described in Adopting Platform-Ecosystem thinking in your Organization: The 3 Phases, the very first phase for organisations when it comes to realising that the world has shifted from an industrial paradigm to an age of platforms is often refusal. Simone Cicero ingeniously coined the term “NAH” – Not Applicable Here – and this has been very real in the first year of working in the dRural project. Trying to bring 31 diverse partner organisations along to adopt a new language takes time, and, besides, it is something not achievable if not actively sought and wanted by the impacted partners: we knew we had to work on cultural perspectives.

In addition, the strict project proposal – and the need to adhere to ideas put on paper before even starting to explore the ecosystems of the four regions – has been a constant reminder of the legacy thinking inherent in such projects: the kind of cultural debt and entrenched incentives often seen in organisations “stuck” in phase one.

One key message that we continue to stress – including through a first design sprint organised with the regional partners at the beginning of 2021 – is that we are designing the dRural platform for the ecosystem (or several ecosystems in this case). We are not trying to only “solve problems”, but rather help entities to boost their performance based on their existing motivations and goals. This can be tricky to absorb, not the least for service providers who have been traditionally focused on meeting their end-users needs. The need to go beyond such an approach has been well documented already in 2017 in “Why we need to go Beyond the “Customer” Narrative”:

Platform thinking offers a new perspective: the possibility to look at the enormous potential in ecosystems and to design new ways to empower them to share and exchange value, grow their performances, develop new capabilities and — in the end of the day — be able to confront the rising complexity of the post-industrial world.

Without strong motivation, gaining platform thinking literacy can seem futile compared to easier to grasp concepts (we said it above: the refusal and NAH attitude kicks in). But getting stuck in phase one leaves us blind to underlying shifts in society that cannot be ignored: technology becoming pervasive to everything we do on the one hand – pocketized production, open knowledge, as-a-service commodities, low- and no-code – and the need for contextually aware relationships between producers and consumers on the other. And we observed, from thinkers all over the globe, that technology is not the driver (i.e. purely adding “cool emerging techs” is not the kind of innovation we are aiming at, since it’s not sufficient to grant adoption): the key is to add governance layers to lower down adoption thresholds, and maximize the return on the adoption curve. Those unable to embrace those key drivers will simply have fewer chances to thrive in the 21st century.

The phase of platform thinking adoption following refusal is understanding first, and then excitement. In dRural, moving to this phase will require further efforts in 2022. But, we are already starting to see some fruits of the work done so far. One such sign is that we start to hear partners refer to things like network effects and platform strategy more and more frequently.

We found it particularly helpful to use the “story” or narrative element of our platform definitions to nudge partners to adopt platform thinking: what is the galvanising message that will enable a shared context of play? This is something they seemed happy to “make their own” and work towards – another good sign that the shared language starts to find traction.

2. Spotting opportunities among diverse partners and arenas

The second challenge we faced in 2021 was the somewhat weak sense of strategic alignment and contextual awareness among regional partners. When we planned the design sprint in March 2021, we were already aware of one of the strongest “intrinsic limitations” of the service design practices: it’s not enough to put all actors in the same room, nurturing collaborative design practices and attitude, to have automatically a good result. This approach, albeit good in theory, is often based on wrong pre-assumptions that all players already have enough understanding and practical skills in the given context, to let the key points and the key values emerge from the application of a solid framework. We also knew that for most of the partners (see point 1 above) Platform Thinking mindset was pretty new, and thus we would have needed to provide the right and deep enough framing and contextualization for them to be capable of expressing all their richness, capabilities and needs/objectives.

Instead, we started, in any case, the Design Sprint events, mostly for time pressure and willingness to start moving in and for the consortium, and then we found that the partners in each regional ecosystem were quite far from having a shared vision or strategic alignment around what the dRural platform can do for their respective constituents. That’s why, rather than working towards “real” design, the design sprint and its results became more instrumental to building contextual awareness and starting to identify the possible arenas to explore in each regional context.

Luckily, we are not alone in this effort. When it comes to building contextual awareness, the excellent research team from the University of Twente lead the “ecosystem building” work of the project, carrying out in-depth interviews and workshops with ecosystem entities. This helps us to derive important insights for our design work. Albeit a quite unorthodox way for us to work, since we are not in direct touch with the ecosystem, we are confident that it’s moving in the right direction.

As mentioned, regional partners are still in a divergent phase of exploration. Our next steps together in 2022 will be to try to help them gain more clarity on the concrete platformization spaces to start from in each region. We have some preliminary insights from the ecosystems and we are now starting from key “arenas” that have been identified as a priority in the different regional contexts.

To guide this work, we use our Platform Opportunity Exploration Guide – POE Guide – which essentially outlines two broad approaches to ecosystem exploration: Ecosystem Mobilization and Product and Services Innovation. In the case of dRural, we need to mix both approaches depending on each regional situation. In some regions, Ecosystem Mobilization is probably more suitable since the opportunities sought are new, while for other partners the project is mainly about finding new ways to deliver services – extending their regular offerings.

Regardless of which approach we take, the “mother question” described in the POE guide is the same: if I have a broad space of opportunity, where am I supposed to start from? This is where the key steps of our platform opportunity exploration come in handy.

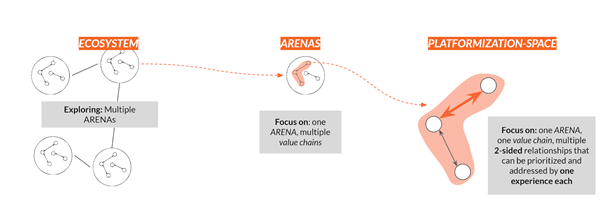

We start by looking at each regional ecosystem through the lens of the partners who collaborate in the project. Based on their combined activities, markets, and value chains, our next challenge is to find the key arenas and platformization spaces that can be the “best bets” for their platform strategies.

The Arena concept – whose definition we have adapted from Rita McGrath – is useful here, as it is “characterized by particular connections between customers and solutions, not by the conventional descriptions of offerings that are near substitutes for one another”. As such, it hints more towards markets or customer groups that an organization is targeting in that specific moment. Accordingly, we define arenas as: Multiple two-sided relationships, or even multi-sided relationships, between (tens of) entities that engage in achieving certain clusters of jobs-to-be-done (see our POE Guide p. 30 for a more detailed explanation).

So, what are we understanding about the regional ecosystems and their arenas so far?

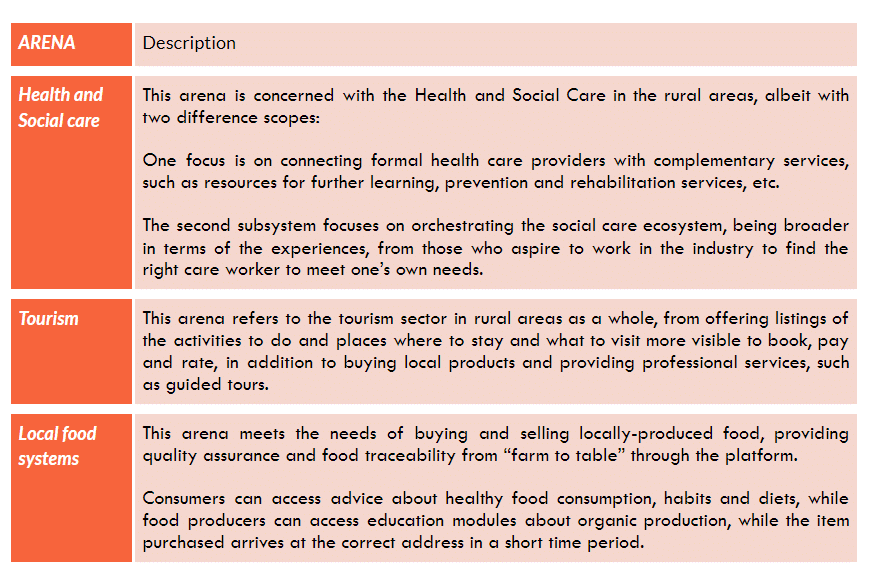

Based on the design sprint, we identified six fields that we analysed from an arena lens, even if some of these may fit more or less well with the actual definition. Those were: health and social care (divided into two subsystems of health and social care), tourism, local food systems, transport and mobility, business development support and e-government services. Those six fields provided a starting point, however, after additional insights around the regional priorities and ecosystem players, we start to see three arenas coming across as distinctly more strategic: those to further in our more detailed analysis of value chains and platformization spaces.

These “top three” arenas are briefly described below. Due to partners’ confidentiality and considering that this is a work in progress, we don’t associate any regional partners with these results yet. We hope to be able to share more concrete details over the course of next year.

Our next steps will be to work with regional partners – as well as project research partners like the University of Twente, the research institute RISE and ICONs – to start sketching the more detailed picture of the platformization spaces and jobs-to-be-done in the above-mentioned arenas. Then, together with the partners, we’ll move to the design of actual platform experiences.

While embarking on the next steps, we have some further complications and constraints imposed by the project, which we describe below in the third and final key learning of the year.

3. Using “fixed” parameters strategically

An issue that many of our readers have probably already faced when dealing with designing platform strategies and building suitable technologies (and not only), is that a portion of the technology may already be largely defined or implemented. How can we still “listen” to the ecosystem, absorb the new information and translate it into an updated, improved version of the platform?

Let’s start step by step: we are dealing with a complex project in which many different partners engage and work towards its implementation. It also requires adapting it to the existing regulations (i.e. ethics and data), and it deals with local and regional administrations that are spread around Europe and have different systems and ways of working.

To simplify, it is like building a house: if you haven’t laid the foundations yet, it is easier to modify or change the project altogether. Once you have built the pillars, you have less freedom to change the layout of the interiors. Likewise, when you have built the internal walls, your freedom to choose different options shrinks. Perhaps you could still be able to change the furniture, but changing the structure of the house itself can be not possible, not convenient at all, or too lengthy, depending on other constraints you have, such as time and budget. This is even more true when the project is highly customised, hence specific features are added to address needs and requests; in the case that they are not needed anymore or they happen not to be as valuable as it was previously expected, it will be more complicated to do something different with these features that have already been implemented. Either way, assessing which stage you are in will make the difference to decide what and how to develop further.

When the dRural project started, it was defined by certain constraints and pre-set features. For this reason, simple services – provided through the marketplace – provide access to the platform and other “horizontal services”. As such, they can have commonalities for all the regions. Based on the design sprint we ran in March 2021, we gave some illustrative examples of possible simple service use cases to guide its development. To what extent those inputs will be used by the developers in the first MVP remains to be seen.

Instead, complex services have a higher degree of customisation and they are likely to vary region by region. Picking such services is more complicated and needs to take into account various factors. First of all, the core meta platform architecture already exists, and hence provides the boundaries for what type of data platforms can be integrated into the dRural platform. This causes some potential friction, especially for the health and social care services arenas, where special data management protocols and certifications are needed.

Secondly, the platform needs to be self-sustaining over time. Not only the services offered by the platform must be feasible in terms of technical capabilities, timeframe, and be needed, but they ought to contribute to the long-term sustainability of the dRural platform and its regional variations. This is an added challenge that requires additional cost modelling and planning while customising features for the target users in each region. The value captured by the platform must balance the incentives provided to the supply and demand sides to join it and keep interacting inside of it.

Our position to contribute to value creation for dRural? We know (check for instance The 3 Key Challenges in making your Organization Platform-ready ) that Platforms in complex environments normally work at the three value creation layers: the niche, fragmented ecosystem where producers and consumers meet; the producers-of-value oriented interface, helping the producing side to connect with components and enabling services, through what we call the product side of the platform, aiming at providing a unique, coherent main UX for the users; and the extension platform pattern (see the quote below). Thinking in this way, guide us to think of, and provide a marketplace layer where niche producers and consumers can connect (our simple services case), but also a “core set of enabling features that are potentially complemented by an ecosystem of third parties”. Since these enabling services and channels can be way too many, we need to reduce the scope, and we did this by working on a few vertical prototypes/templates of platform cases, especially for the complex services. Finally, very important for having a future proof platform, the enabling elements and components (resources, commodities, services) must be released to the ecosystem in such a way that pro-active entities are engaged in the use of these tools and can innovate by adopting them and inserting them in their value creation pattern. These enabling interfaces can also attract further entities, like software or processes developers, in the Extension Platform Pattern:

These third parties normally develop additional complements in the form of “extensions” (thus the idea of an “extension platforms”) of the core set of features, something we can call the “main UX” that the platform provides to its users.

This hence begs the question of whether the predetermined dRural Core Meta Platform will provide the right “main UX” for dRural in the long term, and how can we maximise its chances of doing so?

Stay tuned for our next insights in 2022

To explore the above questions, we will work with each region and the information we already gathered so far. As of now, there are still many options to be considered for every region to define its complex services and how they will contribute to the overall platform strategies. A lot needs to be defined during the first quarter of 2022 when we will guide the regional promoters to pick the services that end up being tailored for their unique characteristics and being sustainable over time.

One thing is certain: when we venture out from our community of practice into new ecosystems like the ones surrounding dRural, the design process becomes entangled in a lot of “noise” and negotiations that we are learning to best deal with. We try to do so with a dose of humbleness yet determination that some of our experience needs to be thoughtfully considered if the project should have a chance on the transformational impact it seeks.

Before You Go!

If you have similar experiences to what we describe in this post (e.g. you have overcome some of the challenges described), or if you are a platform domain expert in any of the top three arenas of health, tourism and local food systems, we would like to hear from you!

Please reach out at drural@platformdesigntoolkit.com.